Falling exports add to a litany of trouble facing China’s economy that includes weaker foreign investment and capital outflows

(Originally published July 14 in “What in the World“) China’s exports in the second quarter of 2023 fell 4.4% compared to the same three months last year, underscoring how U.S. tensions are heaping pressure on the world’s second-largest economy.

Most media coverage focused on the more volatile monthly data for June, which showed exports falling 12.5% year-on-year after a 7.5% drop in May. While that may suggest an accelerating downturn, quarterly data is more useful for identifying broader economic trends. Monthly data tends to be erratic or “noisy,” heavily affected by seasonal shifts and one-off events.

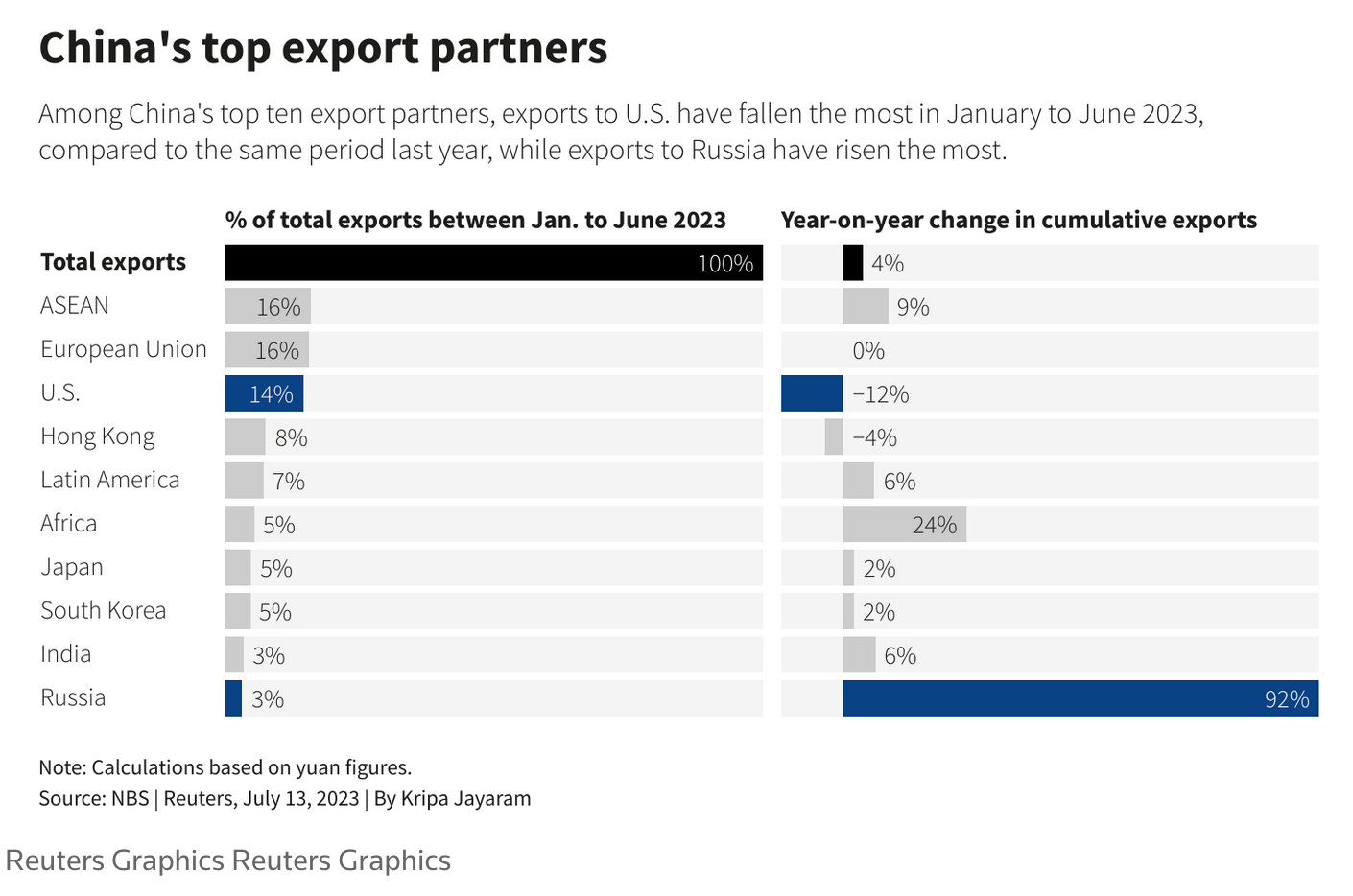

But it’s clear that China is getting no help from exports. Leading the decline are exports to the United States, which fell 12% in the first half of 2023 compared with last year. While June exports to Southeast Asia and the European Union fell by more than 10%, exports in the first six months of 2023 to all of China’s major trading partners but the U.S. grew in the first half—except to Hong Kong (down 4%) and the European Union, where exports were flat.

U.S. tariffs and efforts to reduce American dependence on Chinese imports have pushed bilateral trade with China below that with Canada and Mexico. As detailed in yesterday’s newsletter, bilateral trade between the U.S. and Mexico in the first four months of this year represented more than 15% of all U.S. foreign trade, compared with 12% for U.S.-China trade.

China’s exports to the U.S. fared worse in the first quarter than the second, suggesting they might be recovering somewhat. China’s exports to the U.S. fell 25% in the first quarter, according to U.S. customs data, the second consecutive 25% quarterly decline.

China nevertheless blamed the weaker export data on slowing global demand, which isn’t entirely true. Beijing is trying to remain diplomatic, but U.S. efforts to punish its economy (and U.S. consumers) for China’s perceived transgressions (e.g., espionage, human rights abuses, unfair trade policies, and military assertiveness abroad) are likely to scuttle the White House’s recent efforts to mend fences. So is developing news about a Chinese cyberattack in May and June that reportedly succeeded in hacking into the email account of Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo.

In the latest U.S. overture, Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who visited Beijing only last month, met with Wang Yi, who as director of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee Foreign Affairs Commission Office is China’s top diplomat. Blinken and Wang are in Jakarta to attend a two-day meeting of foreign ministers from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Wang is standing in for China’s Foreign Minister Qin Gang, who is reportedly ill.

Despite the apparent attempts at détente, the Biden Administration is pushing ahead with new rules restricting investment by U.S. private-equity and venture-capital firms in Chinese companies involved in artificial intelligence, quantum computing or semiconductors.

FDI into China already appears in peril, largely from China’s own crackdown on foreign businesses there. Beijing’s official data show inbound FDI grew 4.9% in the first three months of 2023. But in a new report The Wall Street Journal, citing apparently unpublished research by Rhodium Group, says FDI fell 80% in the first quarter.

Foreign investors are also cutting credit to China. According to a new report by the Institute of International Finance, foreign investors sold $1.59 billion in Chinese bonds in June, the sixth consecutive month of net sales. The sales come amid growing concerns about China’s heavily indebted property sector and local governments. Capital outflows by foreign investors and Chinese citizens, combined with weaker FDI and exports, will combine to put further downward pressure on China’s currency.