China buries youth unemployment data as bad news about the economy mounts

(Originally published Aug. 16 in “What in the World“) Nothing does more to torpedo confidence than hiding the truth.

Yet, faced with a litany of worrisome economic data, Beijing took a hard look at its options and decided to bury the one that vexed it most: youth unemployment. The National Bureau of Statistics said it would stop releasing monthly figures for unemployment by age group, including those between 16- and 24-year-olds, which had climbed above 20% to a record high. The Bureau’s spokesperson, Fu Linghui, explained that the youth unemployment figures were being inflated by students who were choosing to stay in school longer and pursue graduate studies.

It is true that the Bureau had discovered huge problems in the youth unemployment data. Specifically, university officials, whose job performance ratings were tied to it, were forcing students to fudge their employment status, resulting in numbers that likely under-reported unemployment among recent graduates.

Fu’s explanation also bears a slight ring of truth: students typically do avoid graduating if job prospects are bleak and, in China, they are bleak. But the real rationale behind dropping the numbers appears to be that they were raising alarm bells about how China’s slowing economy might translate into political trouble, so best to simply eliminate that data as a talking point.

But the move is more likely to sabotage confidence further. As an indication of just that, Goldman Sachs said its global hedge fund clients are already aggressively selling China stocks.

Beijing has long believed it could manipulate the economic narrative by either moving the goalposts, or just removing them altogether. As discussed here last month, Beijing’s GDP reporting has also tended to raise eyebrows among economists. Even in quarters when it was clear to anyone with eyes that growth was stumbling, the economy’s official performance would come in at or near the official target.

Eventually, economists have come to look at China’s GDP numbers as a carefully crafted narrative, like many on TV, “based on a true story.” They may not be spot on, but they are at least “directionally accurate.” Why not just ignore them, then? “Because there is no authoritative alternative.” And at the end of the day, economists must rely on data from somewhere to do their jobs.

Economists have periodically latched onto alternative indicators as proxies for gauging growth trends, like steel production or power consumption. But whenever authorities in Beijing get wind that such an indicator has gained currency, its reporting gets put into a format that make annual comparisons more difficult to calculate—reporting it based on an index, for example, or expressing monthly data relative to a point at the start of the year. Recently, popular indicators have simply disappeared from the official reporting calendar, raising new questions about whether Beijing was trying to whitewash its economic performance.

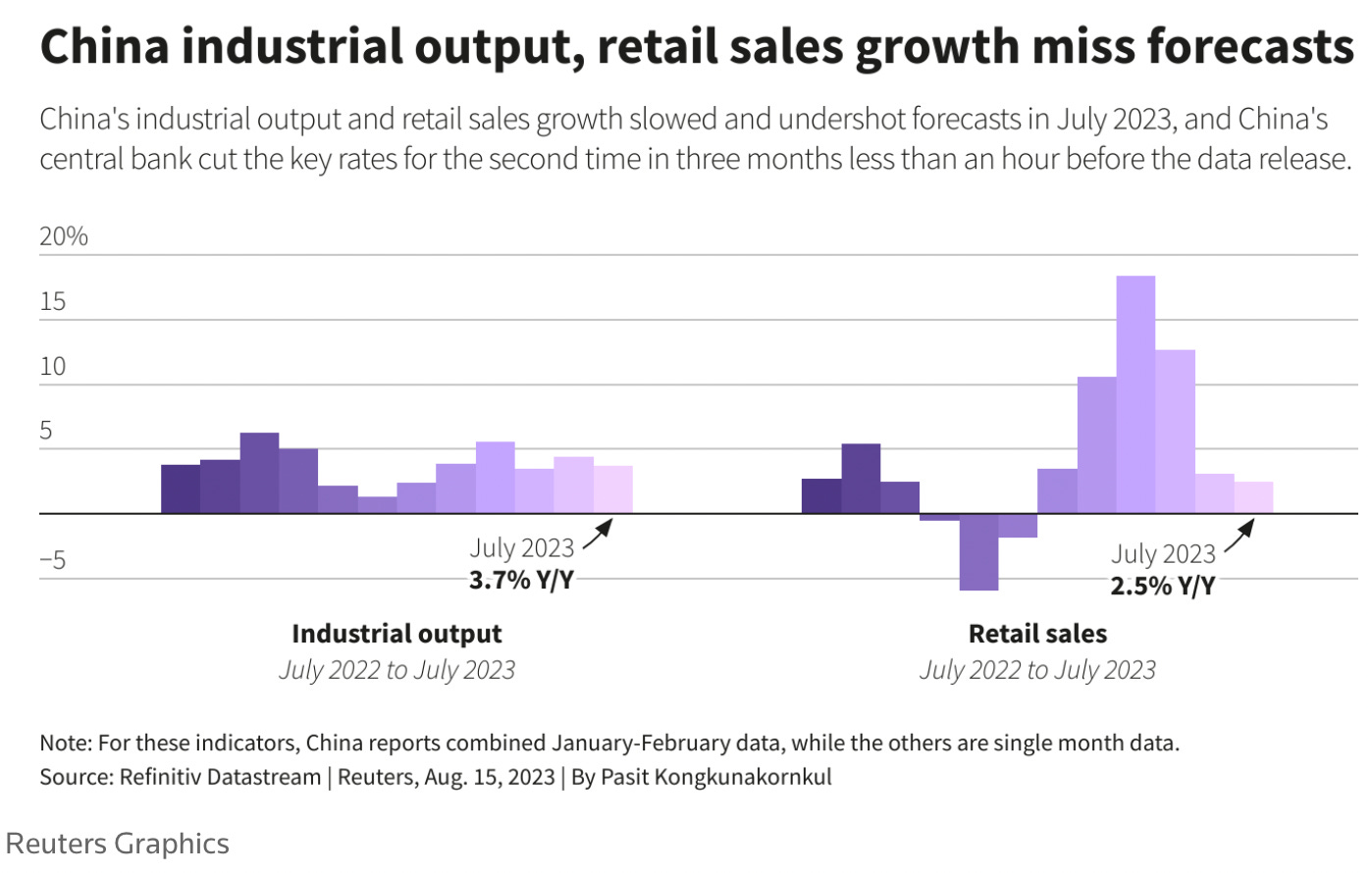

And the latest coat of paint comes as Beijing tries to cover up some ugly numbers. The NBS also said that industrial output, investment and retail sales grew more slowly in July than expected.

The slowdown is hurting property prices and housing sales, which in turn is pushing one of the country’s largest developers toward the brink of bankruptcy. Country Garden, facing at least $1.25 billion in bond repayments next month, is seeking extensions from bondholders for some repayments. The trouble for Country Garden is that its failure could send shock waves through China’s banks and non-bank lenders, as well as decimate the fortunes of the customers who’ve bought Country Garden’s unfinished apartments.

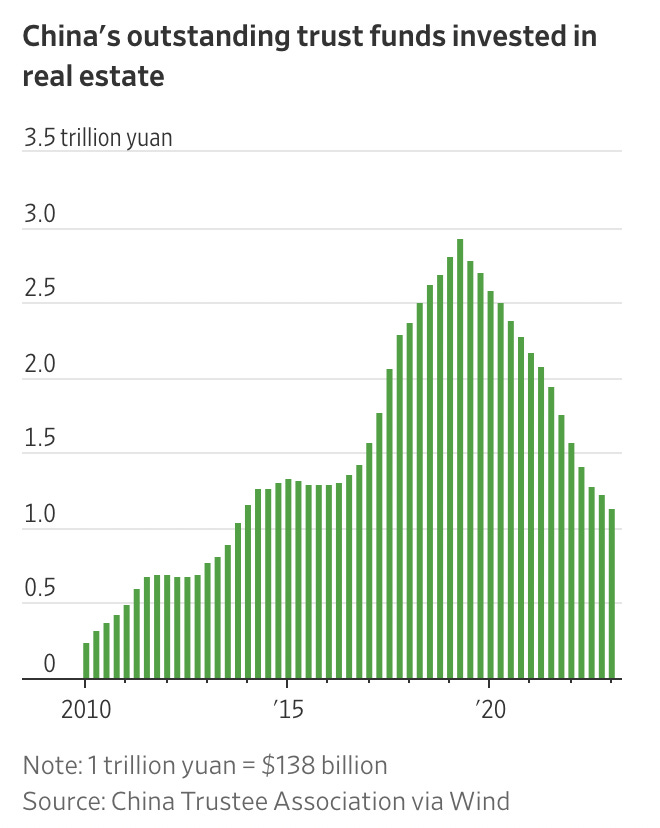

The property contagion is already catching among China’s trust companies. Last week, two companies announced they hadn’t received payments on investment products they bought from Zhongrong International Trust Co.. Trust companies are part of China’s “shadow banking” system, non-banks that replicate banks’ role in providing credit to the private sector. Growth in these trust companies exploded in the past decade as Beijing tried to restrict property lending by banks while encouraging heavily indebted local governments and developers to refinance bank debt by issuing bonds.

Trust companies were the loophole around those bank restrictions. They operate something like banks, but instead of taking deposits, they sell investment products, then either lend that money to property developers, buy property-linked bonds, or take stakes in property projects. Only because anyone with a sound property project could still get funding from banks, trust companies are largely left investing in the riskiest projects that are most exposed to the property downturn and most likely to go belly-up.

The People’s Bank of China responded Tuesday by cutting key interest rates for the second time in three months. The central bank lowered its one-year medium-term lending facility for banks to 2.5%, from 2.65%. It also lowered the rate on seven-day reverse repurchase agreements—essentially one-week, collateralized loans—to 1.8% from 1.9%.