By attacking Ukraine, Russia has declared war on the world’s food security, with the sharpest impact in poor nations where Moscow enjoys the greatest support.

(Originally published April 28 in “What in the World“) Anyone who grew up while the Cold War was still a thing remembers the Ukraine as the “bread basket of the Soviet Union.” Since the early 1990s, the Ukraine has become the bread basket to Europe and the world. Russia is ripping that basket to shreds.

As documented in a excellent article by the Financial Times, farmers have gone to war, roads are ruined, ports blockaded, warehouses wrecked and fields sprout shrapnel and landmines. Fuel from Russia and Belarus farmers use to run tractors is in short supply. The war is blocking not only exports but also the June wheat harvest.

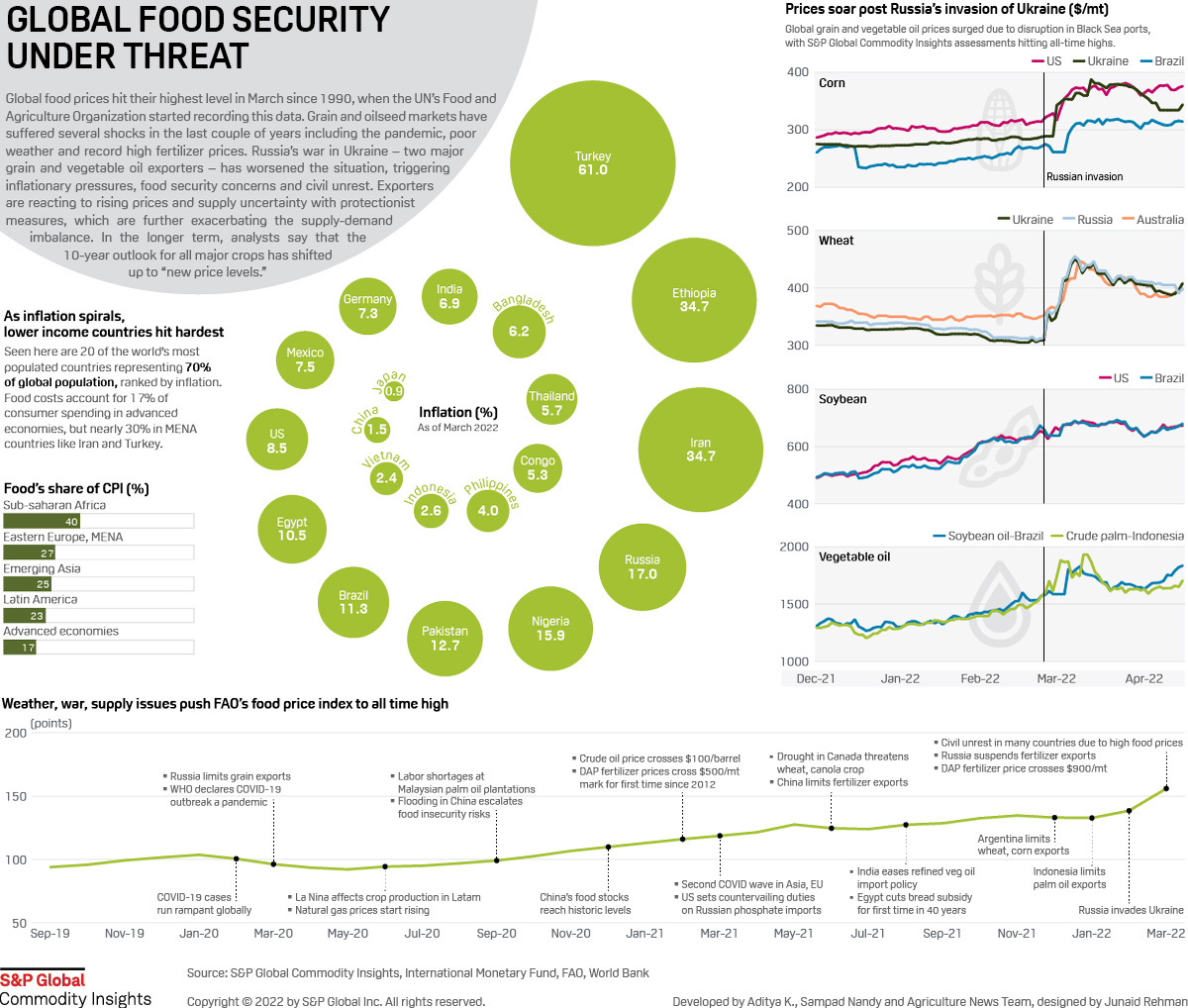

Disrupted wheat exports from Ukraine and Russia are, not surprisingly, pushing up global prices for wheat and flour. But the war’s impact goes well beyond wheat. The disruptions to Ukrainian agricultural exports have pushed global food prices to their highest since the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization first started recording them in 1990.

The Ukraine is the world’s largest exporter of sunflower oil, accounting for 30% of global supply. Rising prices for sunflower oil have spilled over into other edible oils. Indonesia, which supplies 60% of the world’s palm oil, has now expanded its restrictions on exports of palm oil, another cooking oil. Families in Indonesia and across Southeast Asia rely on palm oil as an inexpensive way to cook their meals. But palm oil is also a crucial commodity for industry, used in myriad products from cosmetics to food.

Ukraine is also the world’s third-largest exporter of corn and second-largest exporter of barley. Rising prices for those two commodities are pushing up prices for animal feed, which is likely to pass through into higher prices for meat. Combined with an outbreak of avian flu, that’s likely to push food prices in the United States up 6% this year, according to U.S. Dept. of Agriculture economist Matthew MacLachlan. The resulting surge in prices for wheat and corn has pushed up profits at grain traders such as Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge and Cargill.

Nor is the impact likely to be temporary. The war is preventing farmers from planting next season’s barley, corn and sunflowers. And if Russia succeeds in seizing a land bridge between eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region and Crimea, it will take with it not only more of Ukraine’s productive agricultural land, but two of Ukraine’s seven Black Sea ports and the processing plants nearby.

The impact is likely to be even more acute for China, which relies on Ukraine for almost a quarter of its imports of barley and wheat. From there the impact is rippling outward, hitting the poorest nations the hardest, a recipe for social unrest particularly in the Middle East, where nations like Lebanon and Egypt are particularly dependent on Ukrainian and Russian wheat.