How sabotage of a pipeline in the Baltic and a hurricane in Florida are speeding the world towards a food crisis.

(Originally published Sept. 29 in “What in the World“) Hurricane Ian’s landfall in Florida and natural gas leaking out of a pipeline under the Baltic Sea may have more in common than you might think. They’re both helping increase the threat of a global food crisis.

Gas is leaking under the Baltic after suspected sabotage of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline carrying the volatile fuel from Russia to Germany. Seismologists say they detected two apparent explosions in Danish waters between Sweden and Poland on Sept. 26, after which the Danish military spotted gas bubbles on the surface. While accusations are flying that Russia sabotaged the pipeline in retaliation for Europe’s support of Ukraine, Russia had already cut off gas through the pipeline in early September after months of reduced shipments and intermittent stoppages.

This, of course, raises the question of just what bubbles the Danish are seeing on the Baltic if no gas has been running through the pipeline for most of the month. But let’s assume based on physics that, since it’s the pressure of gas being pushed in at one end of the pipeline that pushes gas out the other, ceasing gas input at one end stops the flow of gas out the other but doesn’t evacuate the pipeline.

So, whodunnit? Well qui bono? Probably not Russia. Some say Moscow would be loath to blow up its own export infrastructure, since doing so would not only make it difficult to revive income if it gets its way on Ukraine, but is a bad advertisement for other customers, notably China. And Nord Stream 1 has been the source of its tremendous leverage over Germany and its reluctance to throw in more convincingly in support of Ukraine with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has, for example, been accused of foot-dragging on military supplies to Kyiv and has drawn the line completely at sending Ukraine battle tanks. Taking Nord Stream 1 down eliminates Russia’s ability to threaten or cajole Germany with gas supplies and thus eliminates the rationale for German hesitation. Point, Ukraine.

Either way, the damage to Nord Stream 1 now virtually assures reduced supplies of natural gas to Europe unless Germany allows Nord Stream 2 to start operations. While the media tends to focus on the threat of a cold winter for European households if the flow of gas is interrupted, it’s German industry that relies most on that gas, and according to Fitch ratings, the chemicals and fertilizer sector is more vulnerable to interruptions than any other. And lest we forget, natural gas, in particular its by-product ammonia, is a core feedstock in the production of fertilizer.

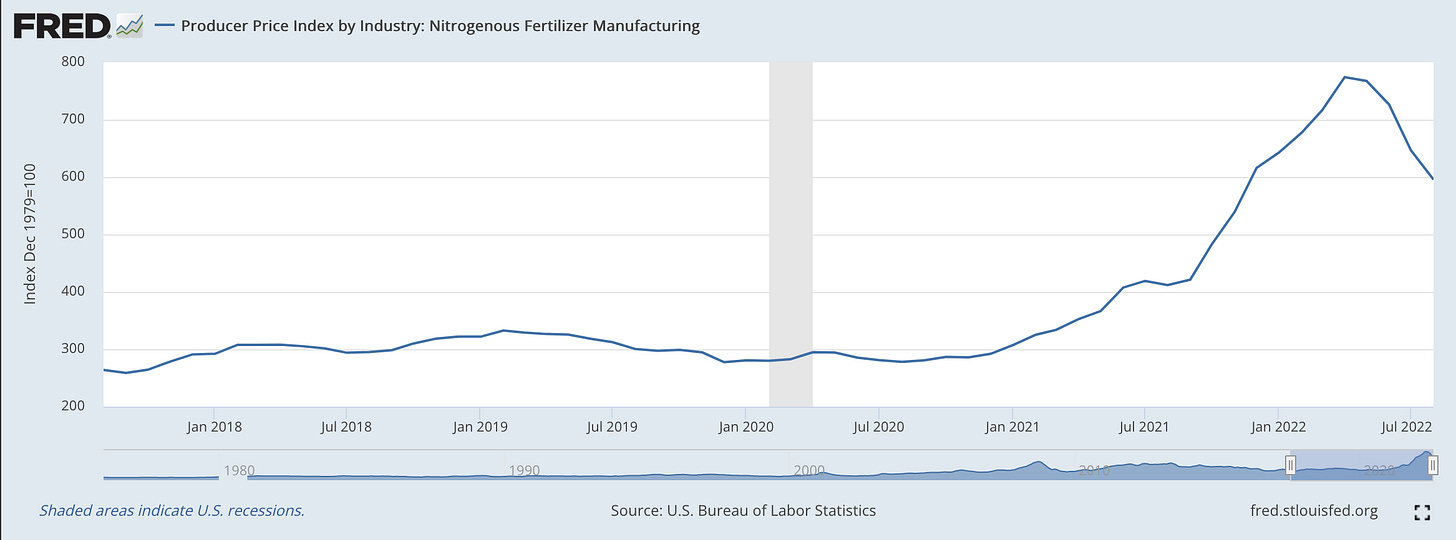

Global fertilizer prices have so high that United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres mentioned them in his remarks opening the General Assembly in New York last week: “To ease the global food crisis, we now must urgently address the global fertilizer market crunch,” he said.

While they’ve fallen back in recent months amid fears of global recession, prices for fertilizer have been climbing for a few years, first because of the pandemic’s disruptions to the global supply chain, and then because sanctions have halted exports from Russia, the world’s largest fertilizer exporter. The sanctions don’t specifically target fertilizer, but by blocking Russia from the global financial network, Russia is unable to export much of anything. When Russia subsequently starting choking off Europe’s supply of its fertilizer feedstock, natural gas, roughly two-thirds of Europe’s fertilizer production was out of commission by the end of August. That was before Nord Stream 1 went off-line.

Europe’s fertilizer shortage, however, has been a boon for America’s fertilizer producers. Last month, the world’s largest fertilizer producing company, Canada’s Nutrien, reported a record $3.6 billion in quarterly profits, but warned that rising natural gas prices would erode its full-year earnings.

One of the world’s other largest fertilizer producers is Mosaic, based in Tampa, Florida. Unlike ammonia-based fertilizer, Mosaic makes fertilizer by mining phosphate from rocks, but it’s fertilizer and so the price of phosphate fertilizer has been soaring, too.

But Mosaic has had to evacuate its employees ahead of Hurricane Ian and the hurricane threatens to inundate the company’s area phosphate mines. That has environmentalists worried that leaking, radioactive water from those “mines,” like the one in 2021 from Piney Point that resulted in massive fish kills, could compound the environmental damage Ian causes. But Ian could disrupt Mosaic’s fertilizer mining and production, exacerbating the global shortage and pushing prices even higher.

“If the fertilizer market is not stabilized, next year’s problem might be food supply itself,” Guterres told the UN. “Without action now, the global fertilizer shortage will quickly morph into a global food shortage.”