China is exporting disinflation to the world. That isn’t good news.

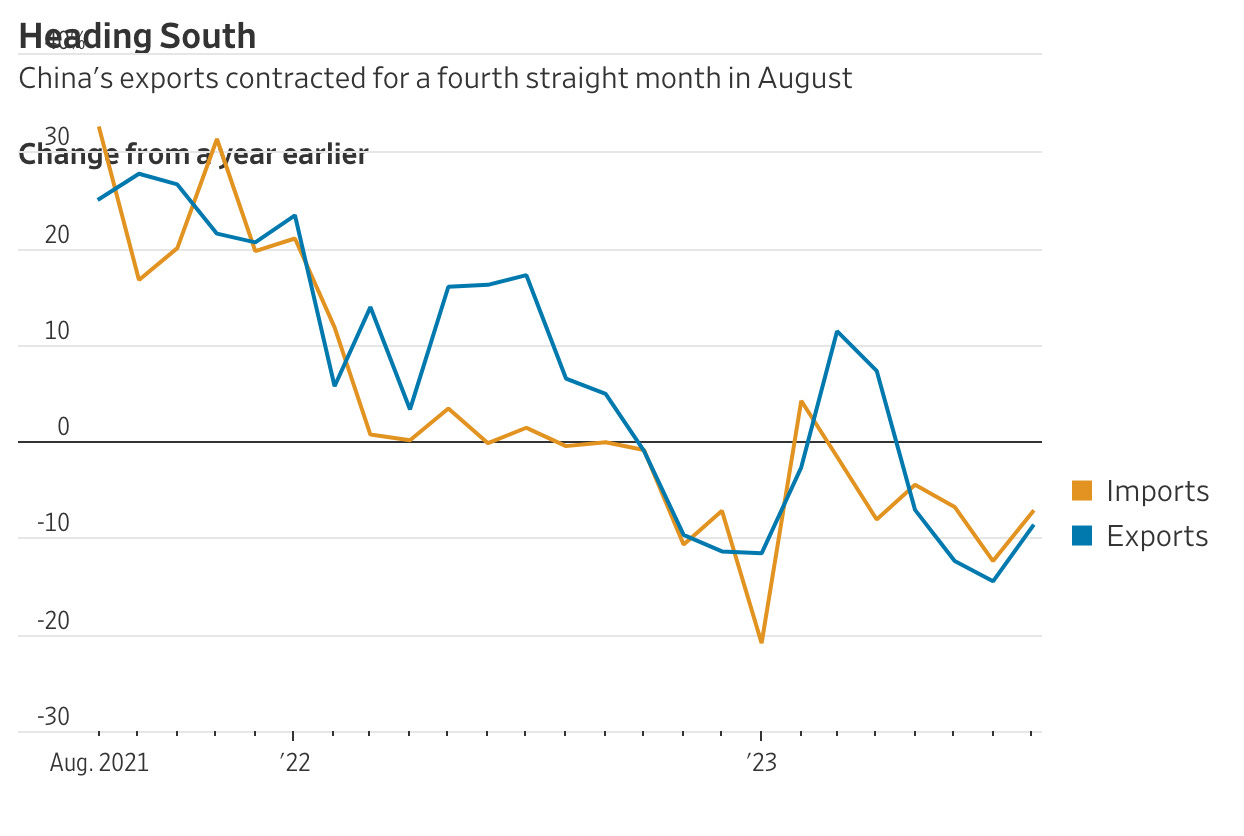

(Originally published Sept. 8 in “What in the World“) China’s exports fell in August for a fourth consecutive month, depriving Beijing of a key engine for reviving growth as the domestic economy continues to shudder.

Exports in U.S. dollar terms dropped 8.8% in August from the same month of 2022, according to the General Administration of Customs. As usual, media reports focused on the volatile monthly figure, with most failing to even mention the export amount—it was $284.9 billion. On a rolling, quarterly basis, China’s exports dropped 7.8%, suggesting that the export slump is indeed worsening.

The poor export data helped push China’s renminbi to its lowest against the U.S. dollar since 2007. A weaker yuan helps China’s exports, so the falling yuan will make those slumping U.S. dollar trade revenues go further back home in China. Indeed, August exports denominated in renminbi fell just 3.2%. More troubling for the rest of the world is that China’s weakening economy is hurting its demand for imported goods. China’s imports in August fell 7.3% to $216.5 billion as consumers cut spending in the face of weak job growth and falling property prices that threaten to bankrupt China’s heavily indebted developers.

How China will handle the slowdown continues to feed speculation, with The New York Times’ China reporters taking turns ruminating on which problem it might tackle and how. The latest comes from veteran China reporter Chris Buckley, who frames the situation in terms of a dilemma for President Xi Jinping: either Xi must relinquish control to revive the private sector’s animal spirits, or tighten his grip to raise taxes to bail out local governments and the public services they provide. This analysis somehow ignores the possibility that Beijing could do both simultaneously. In the Times’ narrative for China, there is only one pendulum, and it only swings one way at a time.

But Beijing has already begun, in typically ham-fisted fashion, trying to revive entrepreneurship and foreign investment. This month, Beijing created a new private-sector agency dedicated to coordinating policies promoting the private sector. Because, you know, there’s nothing that stimulates private investment like a thicket of new government policies. That follows a meeting in late-August between the China Securities and Regulatory Commission and a handful of global asset managers to talk up the country’s prospects.

And Beijing began easing up months ago on its ill-timed, 2020 crackdown of China’s tech sector. Whether it can revive the sector’s animal spirits, however, is up for debate. With the economy so weak, the environment for new investment isn’t exactly ripe. And pundits like Adam Posen at the Peterson Institute believe Xi has killed them off completely.

Xi launched the crackdown at the peak of the tech industry’s hubris in 2020. That year, Alibaba CEO Jack Ma featured at No. 20 on Forbes’ list of global billionaires, with an estimated net worth of $39 billion. Tencent CEO Ma Huateng was even higher at No. 17 with an estimated net worth of $45.3 billion. Alibaba’s financial offspring, Ant, was days away from a $37 billion IPO in Hong Kong when Jack Ma took the opportunity at a conference in Shanghai, with the rest of the country locked down against Covid, to famously taunt regulators.

While Ma’s comments were a trigger, the regulatory crackdown had been building for a long time. Boffins at the International Monetary Fund had for years been warning China’s financial regulators about the systemic risk being built up at Ant and other unregulated online non-bank financial companies. Faced with growing evidence that Ant and others were contributing to China’s debt bubble, and with public grumbling about rising income inequality, Beijing ordered Ant to scotch its IPO and imposed a raft of new restrictions on “fintech.” Jack Ma, who was already stepping aside at Alibaba before he opened his big mouth in Shanghai and sabotaged it, went into a long, self-imposed exile.

Now, with China’s tech titans successfully chastened and their remarkable hubris conveniently forgotten, that entire episode is being cast as part of a more sinister narrative about how Xi has gathered absolute power to himself. Meanwhile, the U.S. Government has launched an antitrust suit against Google, and is planning another against Amazon, after a string of failed antitrust efforts by Biden-appointed head of the Fair Trade Commission, Lina Khan.

But Xi must promote tech, arguably as a counterbalance to Washington’s efforts to stunt China’s technological advance. Relations have become so toxic that even the launch of a new smartphone by Huawei with a domestically produced, 7-nanometer chip, has Washington scrambling to figure out how it might have circumvented sanctions designed to keep it from developing the technology to do so.