From global supply chains to domestic debt, complex connections defy neat solutions

(Originally published Sept. 14 in “What in the World“) Western companies are shifting investment out of China in favor of India, Mexico and Vietnam, but it will take years before they can substantially reduce China’s dominance in their global supply chains, according to a new report by Rhodium Group.

The report’s conclusions jibe with official FDI data from China, which has shown foreign investors joining local counterparts in beating a hasty retreat as China’s economic outlook dims.

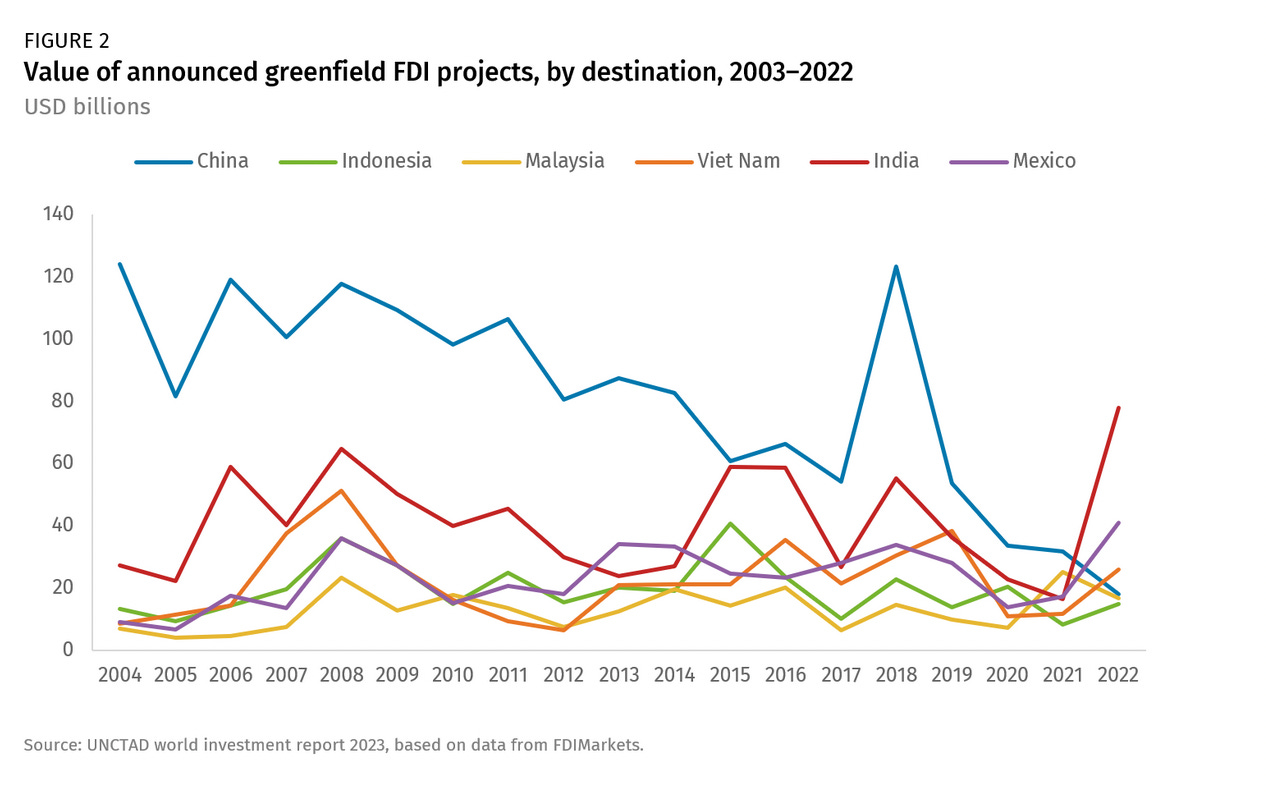

Rhodium’s report uses UNCTAD data to compare bilateral FDI and notes that investment into new, “greenfield” projects in China has plummeted. This would make sense quite apart from their efforts to “de-risk:” Having already built up manufacturing in China, it makes little sense to build new production there. But it also makes little sense to stop producing there either.

And Western companies aren’t the only ones trying to diversify out of China. Chinese companies have for years been responding to rising costs and growing protectionism by moving some of their own lower-end production abroad, particularly to Southeast Asia, the same way Japan and South Korea did long ago. That means supply chains that look like they’re shifting out of China may still ultimately end up right back in China.

But there’s no denying that the world’s manufacturers are trying to diversify out of China. Some of Apple’s new iPhone 15s, for example, will be made in India instead of in China. India now accounts for about 7% of Apple’s total iPhone production. It’s an encouraging start, but not enough to shelter Apple from concerns about a backlash in China against American brands, or warnings by Beijing that iPhones may pose the same kind of security risks that the U.S. has leveled against Huawei’s cellular equipment.

In a newly published book that he completed writing in late-2022, MIT Sloan School of Management Prof. Yasheng Huang blames China’s economic troubles on Beijing’s increasing autocracy, echoing a view articulated by the Peterson Institute for International Economics’ president, Adam Posen. Posen argued that Beijing’s seemingly arbitrary lockdowns during the pandemic convinced China’s populace of their government’s caprice, discouraging private enterprise.

A similar theme now steers The New York Times’ coverage of China, with Times reporters laying the slowdown at the feet of President Xi Jinping and his efforts to centralize decision-making and subject China to one-man rule. The Wall Street Journal blames Xi’s iron grip for inhibiting the government’s response to the economic and financial crisis.

The Times has compared Xi’s increasing power to the kind of personality cult created under Mao Zedong. Huang argues that increased restrictions by Beijing on economic and political freedoms have led historically to economic stagnation.

So, what should Xi do? Economists and investors want Beijing to spearhead an aggressive plan to restructure China’s massive debts, which now amount to roughly 300% of GDP, and supplement it with massive government spending. That would require allowing at least one, large and heavily indebted property developer to go bust, forcing banks and other lenders to write down massive losses on their property loans before paying them back in part with the developer’s liquidated assets. Beijing would then need to inject national funds into bailing out any other developers it deems systemically important to development. Similarly, it might also need to step in and bail out any banks rendered insolvent by their write-downs of property loans.

Rhodium has argued that Beijing is reluctant to do so because the same debt problems (and risk of insolvency) face China’s local governments and their local government financing vehicles, which were created to borrow money and fund their own property development and infrastructure projects. The International Monetary Fund estimates these LGFVs have at least 66 trillion yuan ($9 trillion) in debt, part of 90 trillion yuan in debt owed by local governments overall.

Beijing has for years been trying to encourage local governments to issue bonds to pay down the LGFV debts, thereby shifting the burden from the LGFVs onto their own balance sheets. That increases transparency around who ultimately owes the money, hopefully allowing for lower interest payments when the debt is refinanced. It also helps potentially shifts some of the burden away from bank lending to bond investors. Unfortunately, it’s been banks who’ve been buying most of the local government bonds. As a result, some of those local government bonds are now being used to inject funds into propping up local banks, according to Gavekal Dragonomics.

Besides, refinancing all that provincial and municipal debt doesn’t reduce it, it only keeps it rolling over until hopefully the projects it financed make enough money to pay it off. In China’s current economic climate, that day seems to be getting farther and farther off.

The local government and LGFV debts aren’t technically owed by Beijing, but they are what bankers call “contingent liabilities,” in that lenders basically assumed when making the loans that Beijing backed the borrowers. If Beijing does back the borrowers rather than let those local governments and their LGFVs go broke, its own debts would jump from just over 20% of GDP to well over 120% of GDP, according to Rhodium. Not only that, but Beijing would likely have to take over paying for vital public services now provided by local governments, including healthcare.

Reuters Breakingviews argues in an intriguing new column, however, that Beijing can afford to force the LGFVs to restructure their debt. Breakingviews’ columnist uses a lower estimate of LGFV debt than the IMF’s 66 trillion yuan—instead using an estimate of 54.2 trillion yuan from China’s Guosheng Securities.

Breakingviews calculates that LGFV’s could pay down their debts in a fire sale of their estimated 133 trillion yuan in assets. Even if they were only able to unload those assets at 20% of that value, they’d be able to pay off all their bonds. If they managed to sell them for 30%, they’d be able to pay down all their interest-bearing debt.

Some LGFVs would inevitably go bust in the process, but BV argues that China’s banks can take the hit. Using an estimate by S&P Global that banks might have to restructure 20 trillion yuan of LGFV loans, BV calculates that banks would have to suffer 5 trillion yuan in losses, but even that would still leave their capital adequacy ratios above the legal minimum, meaning they’d still be technically solvent.

There are some immediate problems with this appraisal. For starters, it’s not clear how writing down their LGFV loans might affect banks’ other prudential ratios. CAR isn’t the only limit banks must preserve: the biggest banks also face rules on leverage, liquidity, and interest-rate exposure. Lower LGFV exposures might force them to unwind loans to riskier borrowers that don’t enjoy implicit government backing.

It’s also unclear what investors would be able to buy those LGFV assets given rules about who can own key infrastructure or property in China. That was a problem in Thailand during the 1997-1998 financial crisis: when borrowers tried to sell land, they ran into rules prohibiting land ownership by foreigners. Beijing may turn out to be the only eligible buyer for the LGFV assets. BV’s 20%-30% recovery rate might still be feasible in such a limited market—indeed Beijing might choose to pay a taxpayer-subsidized premium—but it brings us back to Rhodium’s concerns about Beijing’s own fiscal heft.

It’s also likely that any fire sale by LGFVs would send values of other collateral crashing, triggering a much wider restructuring than the S&P estimate that BV uses. That also happened in in the Asian financial crisis when governments submitted to the IMF’s recommendations and forced big borrowers to dump assets to repay banks. It drove other borrowers into default. BV’s analysis doesn’t appear to include this wider hit to banks when a fire sale of assets inevitably spreads to other borrowers like property developers.

Breakingviews might have thus found a tempting solution to the LGFV problem. But the LGFV’s are only one piece of the Jenga puzzle China’s economy poses to Beijing.