Beijing frets over childless women while the U.S. orders cannons and sells fodder

(Originally published Jan. 8 in “What in the World“) Mao famously reminded his countrymen that “women hold up half the sky.” China’s women have taken stock of the country’s outlook and apparently decided to hold up on having more Chinese.

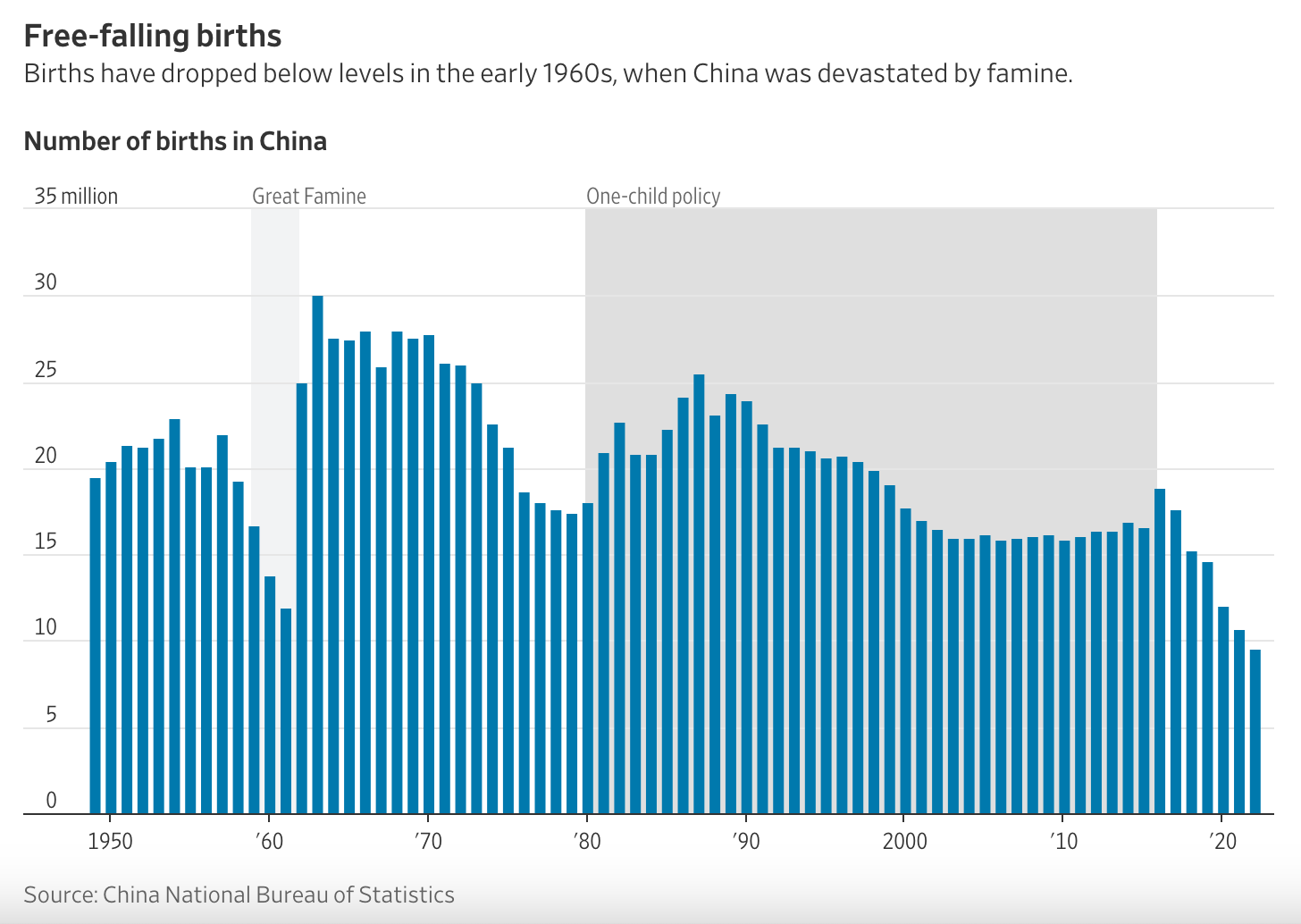

Women in China gave birth to less than 10 million new citizens in 2022, down from 16 million in 2012, according to The Wall Street Journal. That has put China’s population—at 1.412 billion still just barely the largest ahead of India’s—on course to halve by 2100.

Declining population is a problem with which Japan has long grappled. When its own economic bubble was collapsing in the early 1990s, Japan’s birth rate was, too. Today, Japan has the highest proportion among developed nations of 50-year-old women with no children: 27% of women born in 1970 and who turned 21 the year Japan’s bubble collapsed had not given birth by the time they turned 50, according to statistics from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The trend has only accelerated since: the Tokyo-based National Institute of Population and Social Security Research projects that as many as 39% of Japanese women born in 2000 will never have a child.

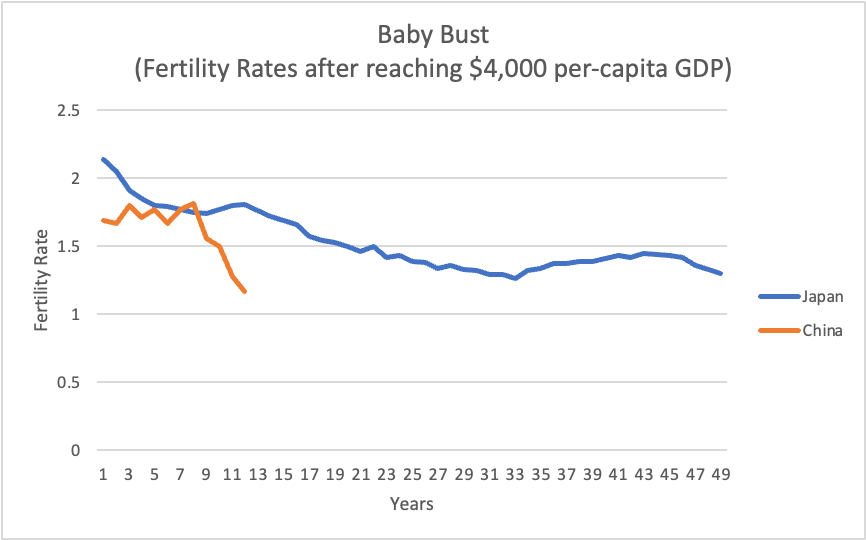

Rather than being merely a symptom of poor financial prospects, however, falling birth rates might also have something to do with rising prosperity. Japan’s birth rate has been declining since 1973, when Japan’s per-capita GDP rose above $4,000 in current US$, a level China reached in 2010. Oddly, female labor force participation in Japan during that decade was also in sharp decline, which seems to challenge the notion that birth rates suffered because women were leaving home to take up work. China’s own fertility rate has been on the decline since the 1960s. But after seeming to bottom out in the late 1990s once China’s one-child policy had been established, China’s fertility rate resumed its steep decline after 2017—despite China ending the one-child policy in 2015. It is now far lower than Japan’s.

Source: World Bank Data

Leaving aside debates about the availability and cost of birth control, common sense dictates that women have fewer children less frequently when they a) can’t afford to (economic hardship), b) don’t need to (don’t live on a subsistence farm where they are vital labor) and c) don’t want to (have achieved a level of affluence that gives them lifestyle and career alternatives beyond motherhood). Both b and c are likely choices when women enjoy greater affluence, which China has enjoyed until very recently until financial stress and affordability took over its narrative.

Considered in this light, one might hypothesize that property bubbles and busts have more impact on birth rates than affluence and poverty. Conversely, stable property prices might have a tighter correlation with birth rates than either household incomes or female labor participation rates. Put simply, rearing young depends on the availability of stable nesting sites.

And in China, falling property prices following the property boom suggest volatility does not favor procreation. The latest effort to stabilize the situation comes from provincial governments, which have borrowed a record 218.3 billion yuan to prop up regional banks exposed to increasing default risk from loans they made for property investments. The local governments raised these funds selling special-purpose bonds, which Beijing introduced in 2020 during the pandemic to give struggling provincial banks a lifeline of capital. The bonds, which are sold by provincial governments, can only be used to inject capital into banks.

Provincial governments also face growing insolvency risks from their own property exposures. Many have relied on property sales to fund public investments and created financial vehicles to do so that borrowed big and now struggle to repay their debt. They pose a major risk to China’s banking system.

Provincial banks hold up to a quarter of China’s bank loans. These smaller lenders are being squeezed not only by falling property prices and rising delinquencies, but by falling profit margins. Smaller banks generally compete by offering lower lending rates. So as China tries to revive growth by cutting key interest rates, their net interest margins—the spread between their cost of borrowing and their lending rates—declines. Net interest margins at urban commercial banks fell in September to a record low 1.6 percentage points.

Banks, of course, aren’t the only lenders exposed to the property problem. Developers, who have relied on rising property prices to borrow heavily to fund new projects, have been teetering. And as Beijing sought to slow credit to the property bubble and reduce the risk to the banking system by imposing lending limits, trust companies stepped in to finance projects when bank loans dried up. So now the trust companies are struggling, too.

War normally drives the development and adoption of new technologies. The war in Ukraine is no exception. But it’s also bringing back old ones.

The U.S. Army has just ordered up $50 million more old-school M777 light howitzer cannons from Britain’s BAE Systems. First developed during the war in Afghanistan as a lighter version of the M198, BAE began winding down production as demand fell over the past decade along with pitched artillery battles. BAE shut down its M777 in Mississippi a decade ago and, after shipping the last M777s to the Army last year, shifted its factory in England to making new submarines.

But the war in Ukraine has emphasized the continued need to blast your enemies into the stone age with simple artillery fire. Almost two years since Russia invaded, the two sides are still blasting each other with artillery and missiles despite making little territorial gains. Ukraine was last fall using its Howitzers to blast 6,000 shells a day at Russian invaders. It has fired so many that the world now faces a shortage of artillery shells, in particular 155mm shells—the ammunition for the M777.

Russia has fired ammo at an even more furious rate, prompting it to call on North Korea for new supplies. Pyongyang must have a prodigious stockpile, because it still had enough to lob a couple hundred this weekend in South Korea’s direction.

Unlike the $1.5 million Paladin M109, which is also made by BAE and drives itself around like a tank, the M777 needs to be towed around. But thanks to the titanium used to make it so much lighter and portable, costs more than $2 million.

The question now is where the Army will get the 155mm ammunition for the M777s. Just before Christmas, the U.S. State Dept. waived the need for Congressional approval to sell $144.5 million worth of the Army’s rapidly diminishing stockpile of 155mm shells to Israel.

There, war continues to spiral outward from Gaza. This weekend, Iran-backed Hezbollah in southern Lebanon fired rockets into Israel from southern to retaliate against Israel’s assassination in Beirut last week of a senior official from Hamas. That assassination was part of Israel’s retaliation against Hamas’ Oct. 7 invasion of Israel. Israel said Hezbollah had fired about 40 rockets and that it had retaliated, apparently using two F-15 fighter jets.