Beijing tries to pump life into China Inc. without feeding the property bubble—or killing the patient.

(Originally published Aug. 21 in “What in the World“) China’s central bank moved Monday to ease credit to businesses while holding lending rates for the beleaguered property sector steady.

The People’s Bank of China cut the one-year loan prime rate, which is the benchmark for bank loans to businesses, to 3.45% from 3.55%. But it left the benchmark for mortgage rates, the five-year loan prime rate, unchanged at 4.2%. This week’s rate cuts follow cuts last week in rates for lending cash to banks.

The decision to hold the five-year rate steady came as a surprise given news Sunday that authorities in Beijing had told the country’s banks to increase credit to the beleaguered property sector, while also promising to coordinate policies to address the simultaneous crisis among heavily indebted local governments. Economists expected the PBoC to follow suit by signaling lower rates for would-be home buyers.

The question therefore looms larger as to just how far Beijing is willing to go to keep the country’s property bubble from bursting, with some now convinced President Xi Jinping is willing to let creative destruction accomplish some much-needed economic reform, risking short-term political dissent for the sake of long-term economic stability.

China’s looming economic and financial crisis has now become sufficiently durable to support full-length analyses of the stakes in mainstream media.

The New York Times warms up with a piece on the looming crisis in China’s property sector, where a bubble of debt has met an intractable downturn in demand to push developers towards the brink of defaults that could torpedo the entire economy. The property sector, the Times reminds us, accounts for more than 25% of China’s total GDP. The Washington Post suggests that Beijing remains reluctant, if not unwilling, to bail out the property sector yet again.

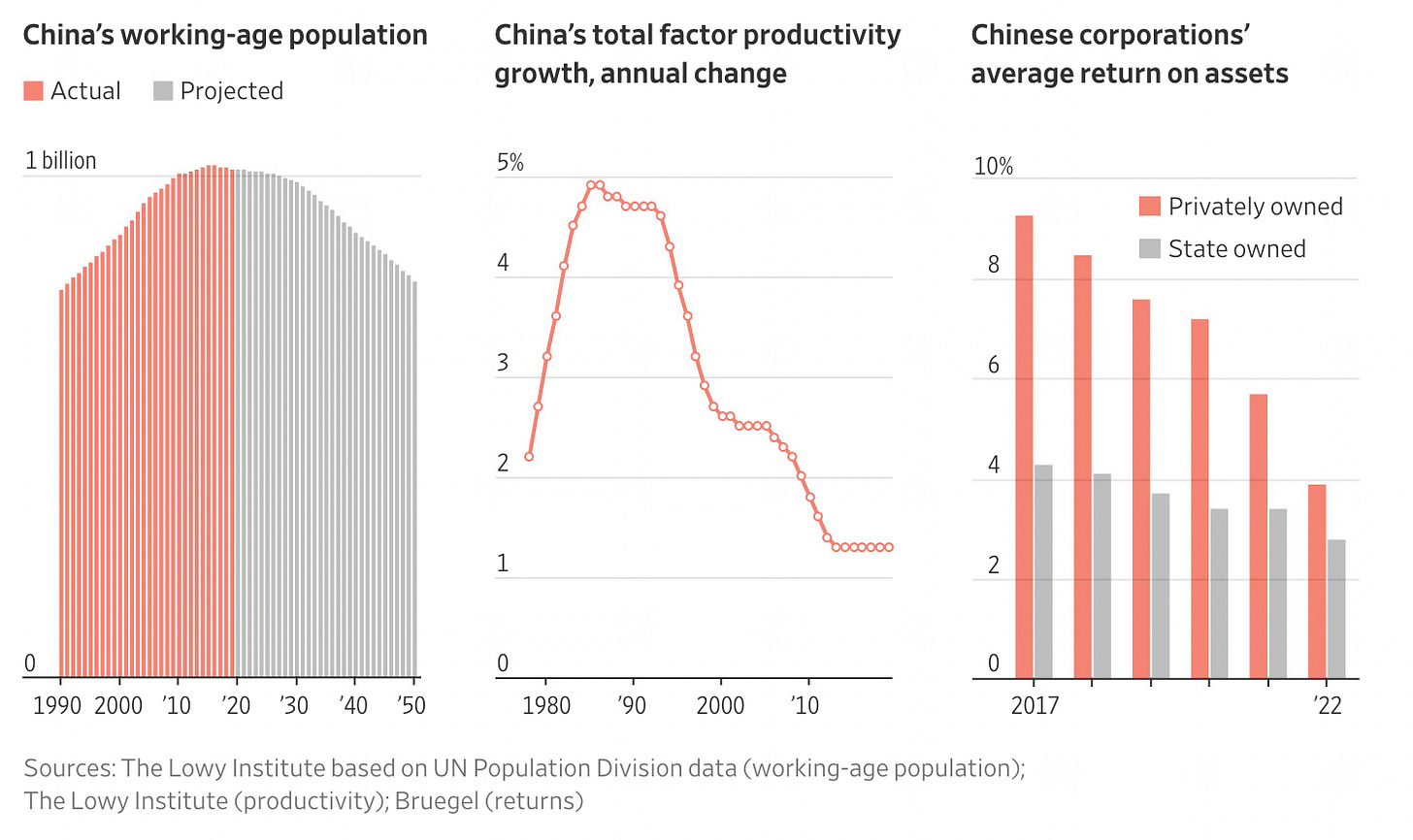

The Wall Street Journal reminds us that China’s property troubles are only part of a much wider problem: China’s shrinking population, falling productivity and the inevitable expiration of a state-led investment model that mirrored Japan’s and now appears likely poop out the same way—long before achieving Japanese levels of prosperity.

A pundit for The Guardian worries this will shake Beijing’s political authority, ending in Soviet-style collapse that rattles the global economy. Bloomberg opines that China’s President Xi Jinping is intentionally letting developers and local governments suffer to break the economy’s reliance on property.

That could make China’s leadership desperate and dangerous, prone to foreign misadventures, as U.S. President Joe Biden warned earlier this month. To illustrate, China announced the usual military drills around Taiwan after the self-ruled island’s vice president stopped over in the United States on his way home after a visit to Paraguay.

But these worries aren’t new. The International Monetary Fund has warned: “The biggest risk is that progress in reining vulnerabilities and advancing structural reforms is too slow and that China, therefore, stays on the old growth path for too long. This would eventually result in a major slowdown in China that would have significant negative spillovers to the global economy.”

The World Bank was slightly more shrill, saying that the “slowdown in China could turn into a disorderly unwinding of financial vulnerabilities with considerable implications for the global economy.”

These warnings weren’t written this year. They were written in 2015. China has been going through a slow-motion financial crisis ever since.

Now, just as then, Beijing faces three scenarios:

The first and most dramatic is that Beijing somehow loses control of the supply of credit to the economy to market forces, which start to price risk appropriately and, risks being high, credit dries up, borrowers default, and a financial crisis ensues, leading to an economic crisis. That’s unlikely because banks do what Beijing tells them and Beijing controls what domestic media report about the banks and their borrowers. A huge borrower like Country Garden might not be able to hide missing bond interest payments to foreign investors, but it could default on a huge loan to domestic banks tomorrow, and no one else might even hear about it.

The second is that China continues to avoid this by following Japan’s example and continuing to “extend and pretend:” that is, keep pouring good credit after bad credit in hopes that growth and property prices recover enough that borrowers are no longer under water, and everyone lives happily ever after. In the meantime, though, real growth is stunted. This “muddle-through” scenario is the most likely because it suits bureaucrats and politicians alike: if you can hold on long enough, it’ll all be someone else’s problem.

The third and most unlikely scenario is that China pursues a middle path, continuing efforts it began almost a decade ago to allow for some defaults and debt-restructurings. That would gradually let the air out of the debt bubble but forcing banks, bondholders, and their shareholders to suffer massive losses. That in turn would likely send the Chinese economy into a painful recession and decimate the savings of a population that uses property as a piggy bank. So, politically difficult, and therefore not the path most politicians would choose. Beijing has resisted because doing so would mean borrowing more money and effectively socializing the debt bubble that was created building the very un-Communist mess China’s economy is in. It would be a massive bailout of the citizens who used debt to build massive fortunes in property and tech at the expense of the poor. In short, it would be a lot like the U.S. response to the global financial crisis—a bailout of the rich to save the entire economy from ruin.

Political expediency and survival instincts have always made option No. 2 the go-to for Beijing. But investors (and Bloomberg and the WaPo) are increasingly convinced Xi has had enough and is now willing to pursue a more radical version that lies somewhere between option No. 3 and option No. 1, allowing for some failures (a la Lehman) and destruction of wealth to put the economy on more stable financial footing.

If he does take China down that path, the result will likely look a lot like the U.S. during its Troubled Asset Relief Program bailout after Lehman—essentially a controlled explosion of the bubble. Instead of continuing to extend credit to failing developers and local governments, Beijing would let them fail and then buy them with taxpayer funds. The question will be whether Beijing can arrest the crisis and restore confidence before devastating the economy for years or triggering a political backlash.