Worries rise for China’s youth as its economic troubles loom over global growth

(Originally published July 26 in “What in the World“) A massive typhoon is due to slam into China’s southeastern coast later this week, a meteorological metaphor for the world’s second-largest economy’s plight.

China’s weakening growth is placing a drag on the entire global economy, the International Monetary Fund warns in a new update to its World Economic Outlook. As China scrambles to revive its faltering economy, attention is being focused on its soaring unemployment, particularly among young people.

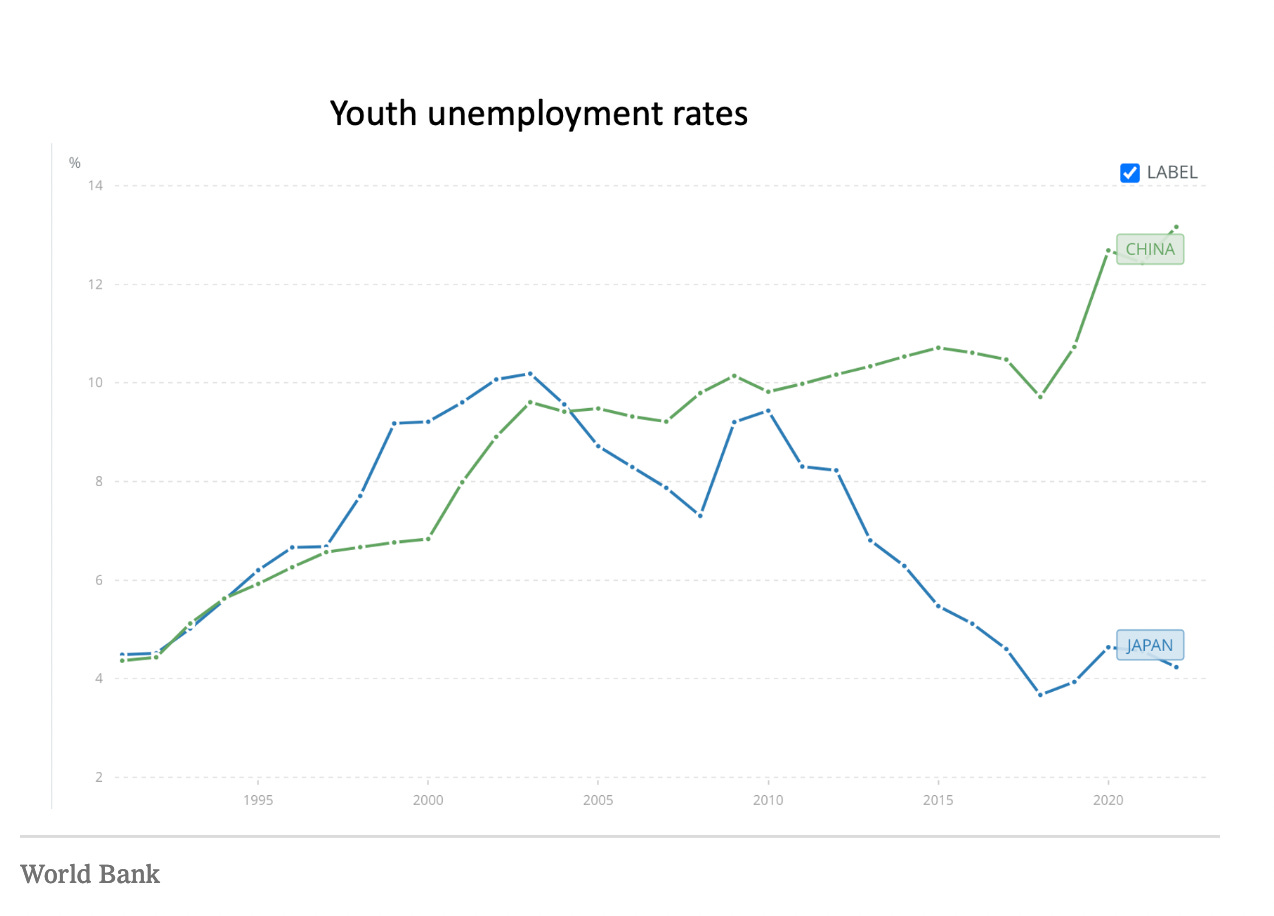

Joblessness among Chinese aged 16 to 24 has climbed above 20%, and many economists believe it is really much higher. That statistic is doubtlessly ringing alarm bells in Beijing, spurring it to take action to stimulate growth. Jobless youth is idle youth, and idle youth can give rise to restless youth, and restless youth is the fuel of political dissent, political unrest, and revolution. Preventing a financial crisis and keeping unemployment from rising significantly higher will be job No. 1 for the People’s Bank of China’s newly appointed governor, Pan Gongsheng.

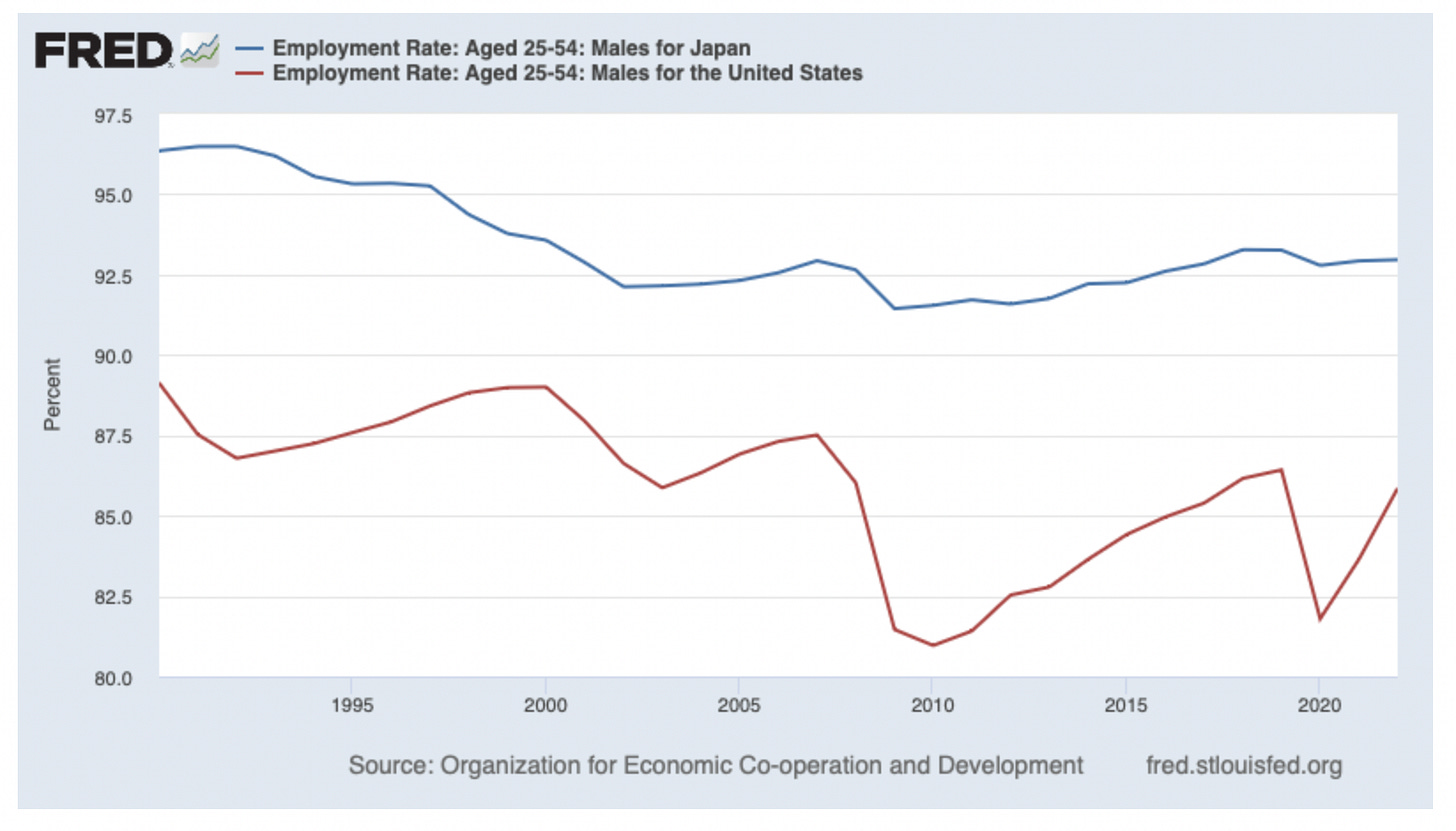

It’s this unemployment problem that makes Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman hypothesize that China’s potential economic slump is likely to be much worse than Japan’s after its own property-debt bubble burst in the early-1990s. Krugman points out that Japan somehow managed to avoid massive unemployment among the folks typically responsible for the most political unrest: men.

Joblessness among China’s youth is already much higher than Japan’s ever was….

Krugman postulates without any evidence other than that China is ruled by authoritarian government that it lacks the social cohesion to pull of what Japan did. Japan is undoubtedly socially cohesive, but it certainly doesn’t seem to follow that Japanese unemployment rates were the result of some kind of collective social action.

Indeed, Japanese underemployment was a severe problem during the country’s “lost decade(s),” as many young people had to resort to part-time jobs, or what nowadays is known as “gig employment” as the small companies that are the real backbone of Japan’s economy adjusted to the weaker growth environment and took advantage of their bargaining position in the labor market to exploit younger workers who hadn’t managed to win the lifetime employment their fathers did. Were they technically employed? Sure. Did they feel financially secure? No way.

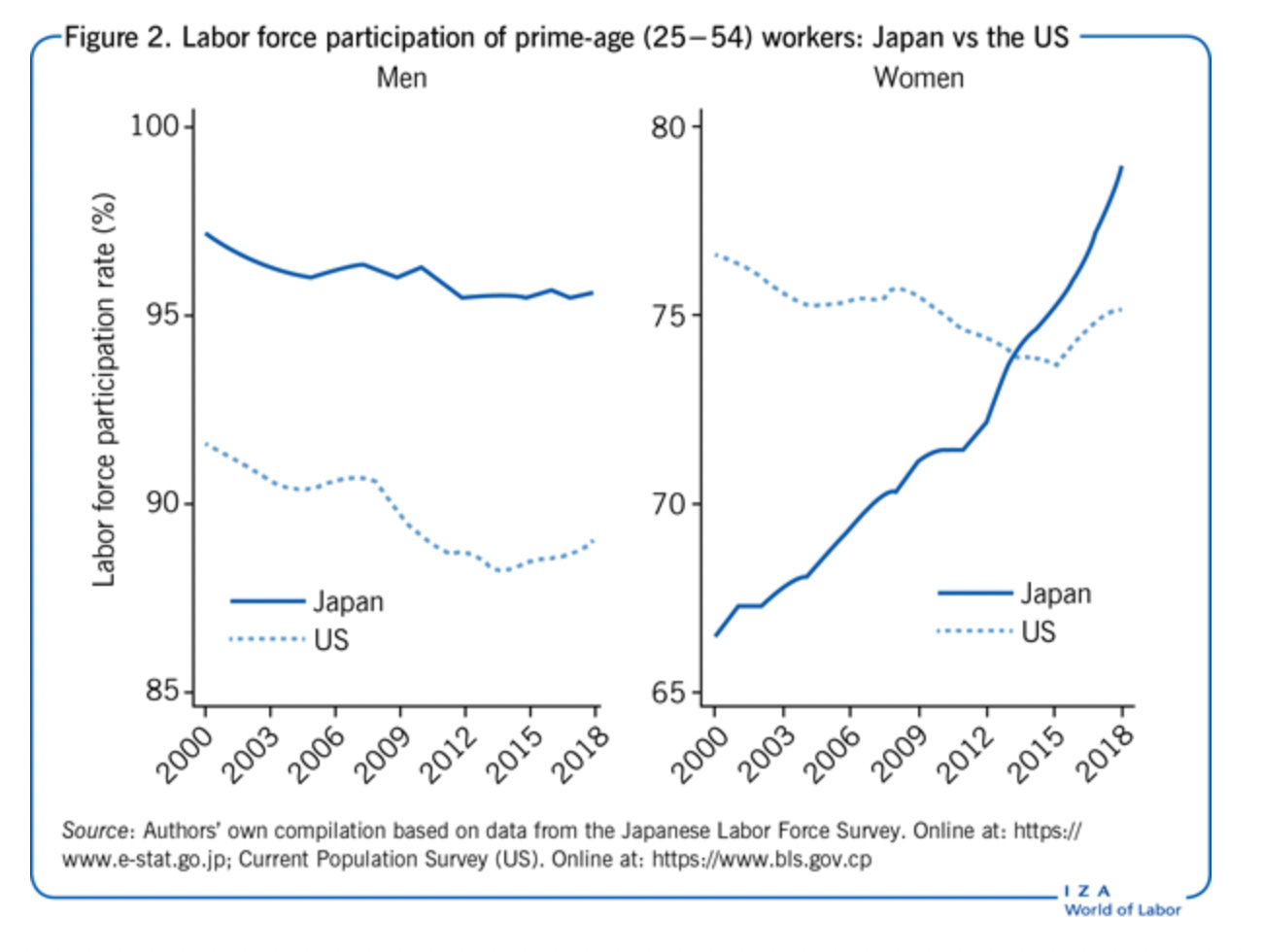

Japan’s unemployment rate was also kept from rising by the fact that there were fewer working age people to employ. Like China has now, Japan then had begun to suffer from low birth rates and a declining population. Japanese employment was also buttressed in the past 20 years by a massive hiring of women into the workforce, according to a 2019 paper by Japanese economists Daiji Kawaguchi and Hiroaki Mori, boosting their labor participation rate nearly 80%, from just over 65%.

China’s own unemployment rates, though for young people already higher than Japan’s was, may eventually be offset by its own demographic dilemma.