Foreign investors pull out of China as its weakening economy deepens its debt hangover

(Originally published Dec. 8 in “What in the World“) Moody’s, the credit rating agency, this week lowered its outlook for China’s creditworthiness to “negative,” from “stable,” citing the rising likelihood that Beijing would need to provide financial support to heavily indebted local and city governments. Wall Street was way ahead of it.

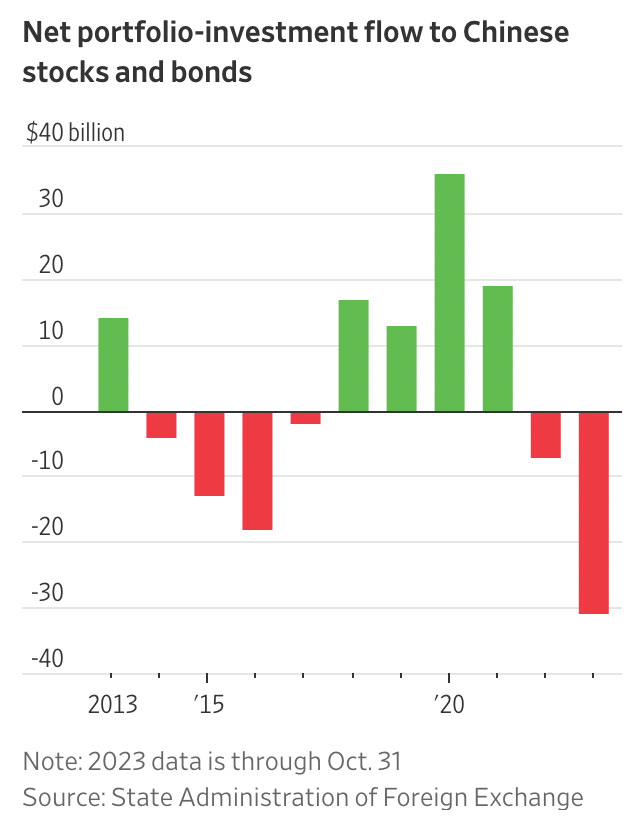

Global investors have sold more than $31 billion worth of China’s stocks and bonds so far this year, according to fund flows data from China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange, as evidence mounts that the engines of its economic growth are dying, leaving it increasingly vulnerable to the mountain of debt it has amassed. The outflows are the largest since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001.

Moody’s rating of China’s creditworthiness remains unchanged, at A1. Lowering its outlook suggests it may be considering a downgrade, however. Moody’s said heavy provincial and government debts posed a “broad downside risks to China’s fiscal, economic and institutional strength,” and “increased risks related to structurally and persistently lower medium-term economic growth and the ongoing downsizing of the property sector.” In other words, local governments pose a contingent liability on the national government, even though the national government offers no explicit guarantee that their creditors will be repaid.

As explained in this space back in September:

The local government and [local government finance vehicle] debts aren’t technically owed by Beijing, but they are what bankers call “contingent liabilities,” in that lenders basically assumed when making the loans that Beijing backed the borrowers. If Beijing does back the borrowers rather than let those local governments and their LGFVs go broke, its own debts would jump from just over 20% of GDP to well over 120% of GDP, according to Rhodium. Not only that, but Beijing would likely have to take over paying for vital public services now provided by local governments, including healthcare.

Typically, a lower outlook isn’t a serious concern. It’s the ratings agency equivalent of a shot across the bow. But if markets are already nervous, lowering an outlook can send investors scurrying. So it’s probably no surprise that China’s state-owned banks were reportedly buying renminbi (likely at the direction of their controlling shareholder) to stem a further slide in the currency’s value after Moody’s announcement. After falling as much as 6% this year against the U.S. dollar amid concerns about China’s weakening economy, the yuan regained some ground in November, but is still 3% lower year-to-date.

It won’t help that multinationals, particularly American ones, are increasingly trying to shift production out of China. Part of this is common sense: it never made sense to have so much of the global supply chain concentrated in China. But since China’s admission to the WTO, it rapidly became the world’s factory. Rising costs prompted many manufacturers, even Chinese ones, over the past decade or so to start shifting to cheaper locations, such as Vietnam. China’s Covid lockdowns, coupled with deteriorating political relationships, has more recently sparked a more rapid movement to “de-couple” from China.

The latest example comes from Apple, which has reportedly told suppliers that it would prefer that batteries for its next smartphone, the iPhone 16, be made in India rather than in China.

The Administration of U.S. President Joe Biden has been trying to accelerate the exit, maintaining Trump-era trade sanctions, and imposing new restrictions in China’s ability to buy advanced semiconductors and the equipment to make them. Republican Party lawmakers are trying to get Biden to go even further. In a report released this week, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives’ Foreign Affairs Committee accused the White House of not doing enough.