As China’s economy lurches, markets fret its leader is willing to let the motherf***er burn

(Originally published Aug. 18 in “What in the World“) China now finds itself confronted by a dilemma: the more it cuts interest rates to revive growth, the more money is likely to flee the country.

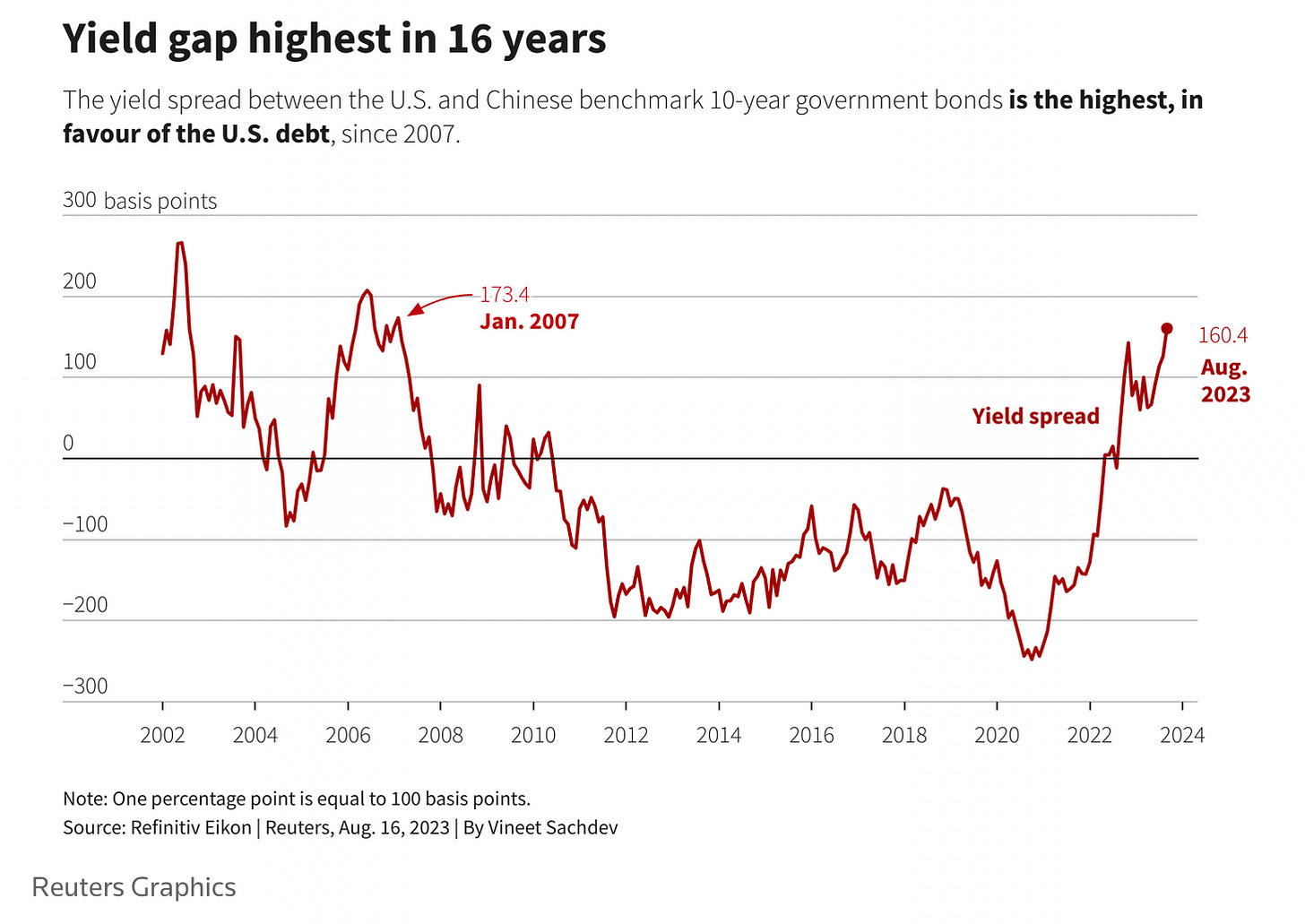

The problem is that China’s borrowing costs are already too low relative to those in the world’s biggest and most liquid bond market: the United States. China’s government is paying about 2.6% to borrow renminbi for 10 years. The U.S. Government pays roughly 4.2% to borrow dollars for the same period. The resulting gap in yield, the spread, has risen to its highest since February 2007—1.64 percentage points.

Keep in mind, China has a closed capital account and a managed currency. That means the People’s Bank of China only allows the yuan to fluctuate about 2% around the exchange rate it determines. And money theoretically can’t flow freely in and out of China. But money is like water: there’s no stopping it from flowing downstream. Investors keep finding new and innovative ways to circumvent China’s controls. Whether the PBoC allows it or not, money will flow towards higher returns, and those flows will result in changes to the real rate of exchange—anyone who remembers China’s black market in foreign exchange can attest.

Because of the yield gap, the Chinese yuan is likely to keep facing further downward pressure in its value against the U.S. dollar. Why? Because Chinese investors will do whatever they can to sell yuan for dollars to buy Treasuries, and U.S.-based investors won’t be very interested in selling dollars to buy yuan to buy China’s bonds. Given the higher yield and the relative safety of U.S. Treasury bonds, most investors would prefer to receive 4.2% to lend dollars than to get just 2.6% to lend Chinese yuan.

The net result is more capital outflows, worsening a flow already underway thanks to falling foreign direct investment in businesses and factories in China. Worse, falling exports means income from trade isn’t offsetting these capital outflows, all of which adds up to further downward pressure on the yuan’s value.

The People’s Bank of China has been cutting rates, but not as aggressively as economists say the economic slowdown and rising deflationary pressures warrant. And fear of capital outflows is the reason.

This is a problem many central banks in smaller, developing economies have grappled with on a much more dramatic scale: the Federal Reserve effectively determines their monetary policy thanks to the speed and size of global capital flows. Thus, when the Fed raises rates, they must respond in kind or risk seeing capital flood out of their own economy, which reduces the supply of money and raises real interest rates and puts the brakes on domestic investment and growth. Conversely, even if they don’t need it, when the Fed starts cutting rates, investors hungry for yield start scouring the planet for better yields. If developing-nation central banks don’t cut rates alongside the Fed, they risk seeing tsunami of incoming capital that stokes inflation and creates asset-price bubbles.

As a result, come central banks—like Turkey’s—have had to adopt a perverse monetary policy tactic: raising rates when they want to stimulate growth and cutting them when they need to cool the flames of inflation.

China’s economy is much larger and its capital controls much tighter. But the PBoC knows that if it cuts rates further, it’s likely to challenge its efforts to keep the yuan from falling faster. Some economists might argue that it should just let the yuan fall: while the first reaction will be capital outflows, eventually the lower yuan will help make China’s exports cheaper and more competitive and boost the cost of imports, helping to reverse deflation.

The problem is that a weaker yuan also raises the relative cost of servicing offshore debt. That isn’t a huge problem for China: unlike many countries it doesn’t have a huge foreign debt exposure. But a falling yuan is forcing some of China’s largest and most heavily indebted property developers—notably Country Garden and China Evergrande—to default on their offshore bonds.

Economists also criticize Beijing for forcing the PBoC to do so much of the work. Like the U.S. government during the era of zero interest rates, economists say, China isn’t doing enough to replace falling private investment and demand with government spending. “The Chinese economy is faced with an imminent downward spiral with the worst yet to come,” Nomura analysts reportedly said in a report this week. “Beijing should play the role of lender of last resort to support some major developers and financial institutions in trouble, and should play the role of spender of last resort to boost aggregate demand.”

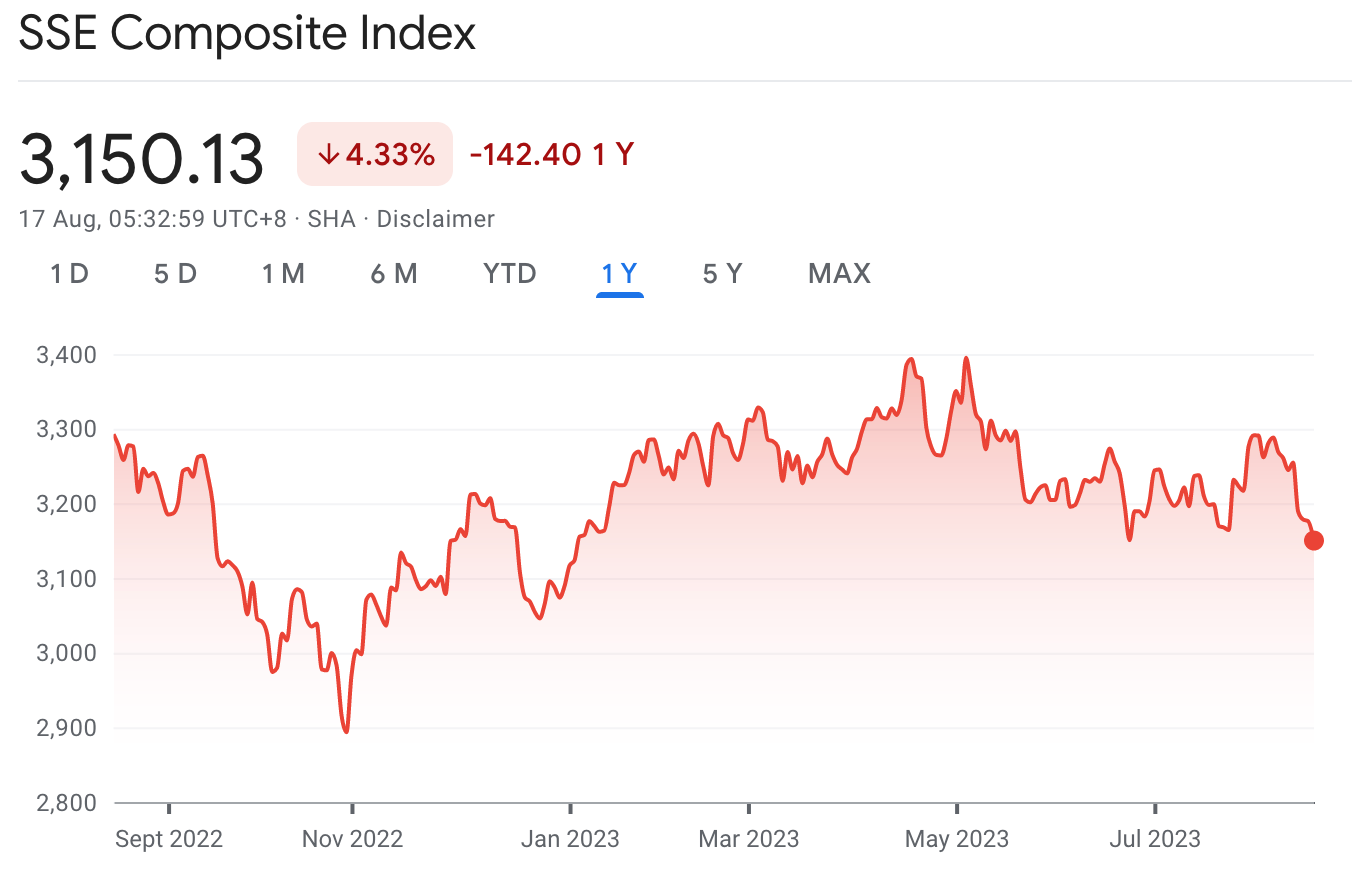

But investors are betting Beijing won’t come to the rescue and are selling stocks. Beijing has resisted because doing so would mean borrowing more money and effectively socializing the debt bubble that was created building the very un-Communist mess China’s economy is in. It would be a massive bailout of the citizens who used debt to build massive fortunes in property and tech at the expense of the poor. In short, it would be a lot like the U.S. response to the global financial crisis—a bailout of the rich to save the entire economy from ruin.

China’s President Xi Jinping is apparently determined not to take China down that path. Instead, he called for patience in his latest speech and urged China’s citizens to eschew the kind of short-term material wealth that has produced “spiritual poverty” in the West and instead to let him “build a socialist ideology with strong cohesion.” The question is whether China’s savers have the stomach for it.

And that is Beijing’s real dilemma.