Hong Kong reaps the harvest of mistrust it sowed; Putin keeps NATO guessing about when he’ll invade Ukraine

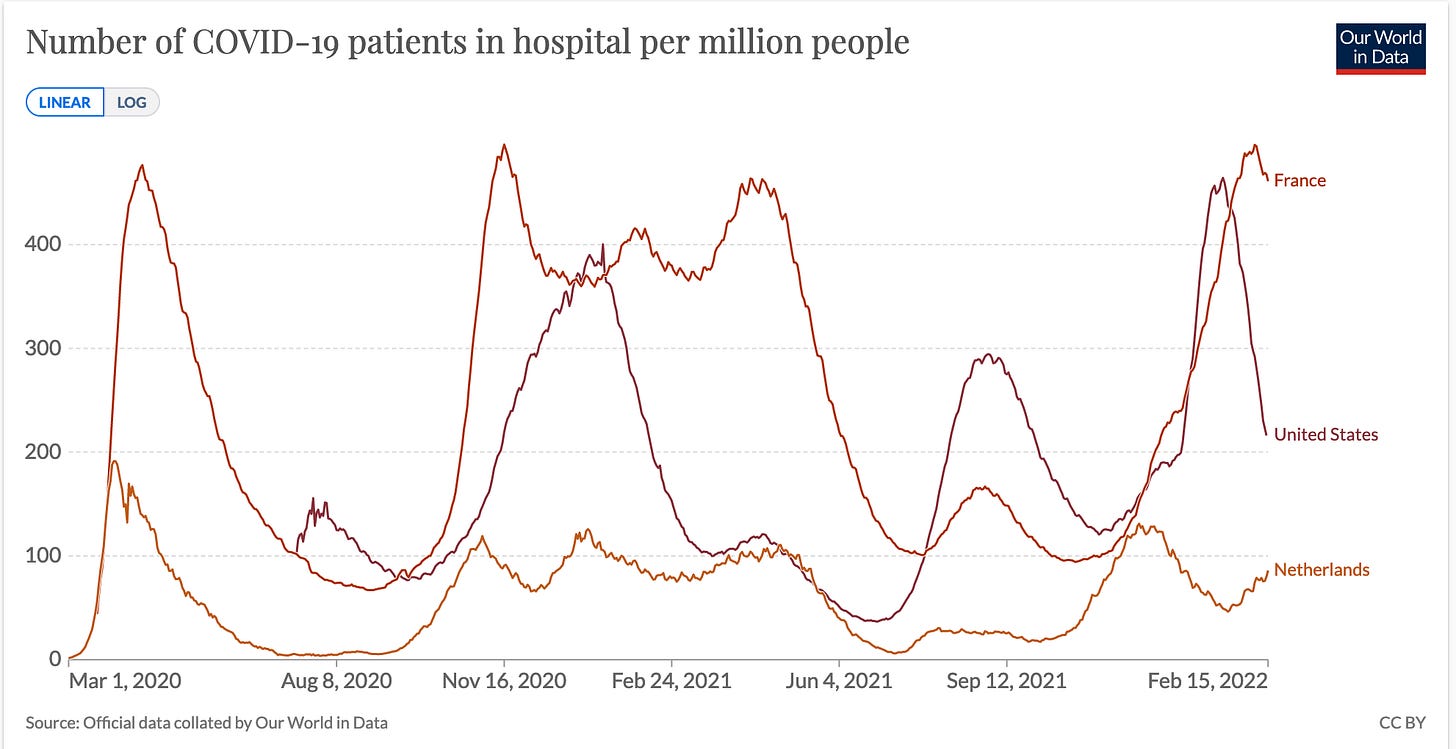

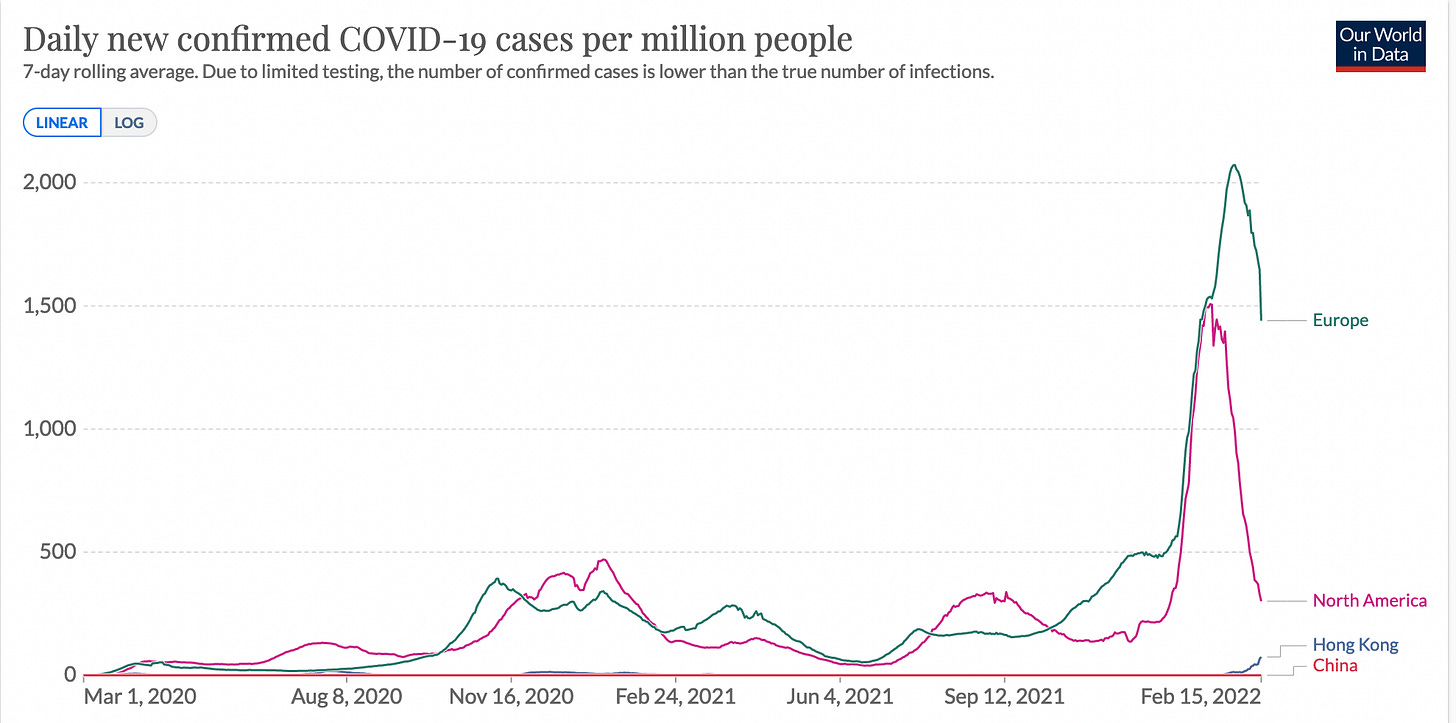

(Originally published Feb. 17 in “What in the World“) As Western nations like France, Germany and the Netherlands continue to surrender to Covid after the failure of half-hearted and ineffective efforts to vaccinate their way to herd immunity, the United States is retreating to a defensive position in which it arms its population with test kits. This is even more ludicrous than promoting vaccines without social distancing: not enough people will take the tests when they ought to, too many self-administered tests will result in errors, and people who test positive can’t be relied on to report their results or self-isolate so they don’t infect others. Why the U.S. continues to rely on individuals to solve a population-wide health crisis remains one of the pandemic’s great mysteries, but the answer seems to lie in how little many Americans trust their government to organize a collective response.

As if anti-vaxxers weren’t enough, the vaccinated seem to have abandoned science for an equally dangerous blind faith in inoculation, forgetting the risks they face with Omicron. The immunity provided by vaccines, and even a booster, is temporary and wanes after about six months, leaving them vulnerable to infection and illness. If infected, even if they don’t fall severely ill, there is still a risk of “long Covid,” including increased risk of heart disease, nerve damage, and according to the latest study, brain fog, depression, and substance use disorders. Oh, and even asymptomatic people can transmit the virus and allow it to mutate.

At the other end of the response spectrum, Hong Kong is being forced to ask China for help applying what The Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip notes is China’s much more effective and less disruptive strategy of localized lockdowns and rapid testing. Unfortunately, Hong Kong has called in the cavalry far too late to be effective.

Hong Kong’s semi-autonomous status has meant that its response to Covid has been only semi-effective. The city imposed one of the world’s most ludicrously excessive quarantines—21 days for most people arriving from most countries—but failed to implement an effective contact tracing or testing regime to mop up those few infections that got through. Worse, it did too little to incentivize or mandate vaccines, which meant its low infection rate only encouraged the reluctant to hold out. Now only 20% of those 80 years old and up have bothered to get the jab. And in a city with a population as aged as Hong Kong—18% of the population is over 65—that makes a big difference. As Regina Ip, a city councilor, told The New York Times:

“In a way we were a victim of our own success because the fatality rate and the infection rate were pretty good until recently… Older people thought they didn’t need to be vaccinated because there could be complications. And the government was hesitant. We have avoided vaccine mandates.”

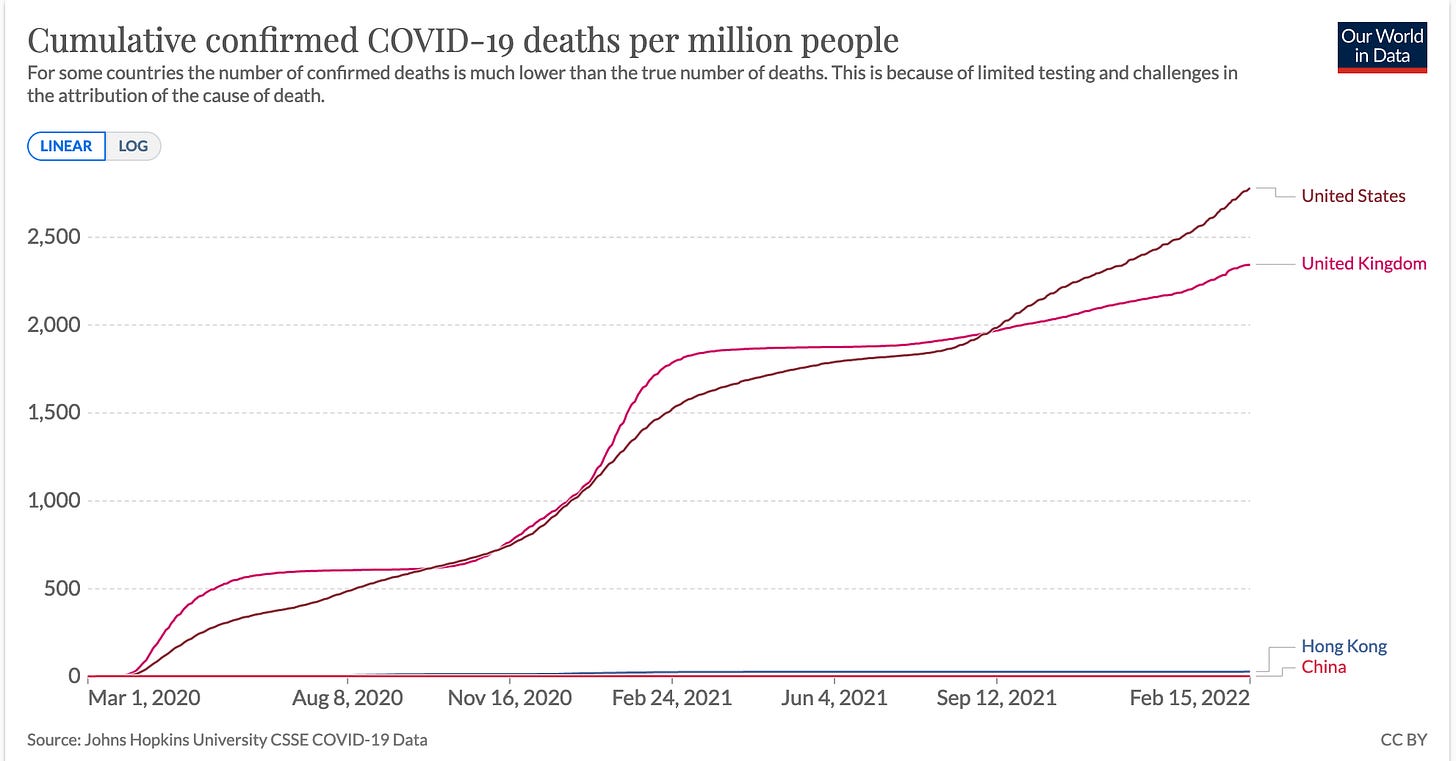

It’s important to remember that even amid what Hong Kong is calling a crisis of new infections, Hong Kong’s case numbers remain much lower than those elsewhere in Asia and several times lower than those in the West, where the pandemic is mistakenly perceived as abating.

While Hong Kong’s rules have succeeded in keeping case numbers and deaths to some of the world’s lowest, they have also deepened public mistrust and resentment with their sometimes comical inconsistency and draconian application. Residents scoff at prohibitions against in-restaurant dining after 6pm, joking that Covid must not be infectious before dark. (Overlooked, of course, is that dinners are most often accompanied by copious alcoholic beverages and the consequent disregard for safety they typically engender.) And they were horrified by requirements that anyone found positive, regardless of symptoms, be hospitalized—a rule that has proved unsustainable as infections rise (but was instituted when Covid was more mysterious and lethal and those who died tended to do so suddenly, even moments after appearing perfectly fine as their oxygen levels crashed). More terrifying was a rule that close contacts of those infected be whisked off for quarantine in a remote and spartan government isolation camp. That rule has also proved impractical as infections—and the number of their contacts—rapidly surpass the number of spaces at the camp.

But it was the quarantine system that has proved the fatal flaw in Hong Kong’s defenses. Most arrivals were cooped up for three weeks in a hotel where they were rigorously supervised and methodically tested. The excessive confinement, however, resulted in hotels packed with arrivals, forcing those already past their 10-14 day period of infection risk to sit for an additional week in a hotel down the hall from others just arrived and still at the peak of their potential infectiousness. This meant more cross-infection, as recent arrivals infected those waiting to leave quarantine and join the general population.

But the true weakness was that quarantine wasn’t applied uniformly to all arrivals, relying on a select few individuals to exercise personal responsibility. To keep flights operating, local flight crews were trusted to quarantine at home for shorter periods. This proved disastrous when two flight attendants violated their quarantines in order to go out and meet family members, thus introducing the highly contagious Omicron strain into Hong Kong’s population.

Once that was accomplished, it was up to Hong Kong’s contact tracing efforts to locate and isolate the resulting clusters of infection. And here, again, its system failed. Anyone who has used Hong Kong’s tracing app “Leave Home Safe” and Singapore’s “Trace Together” knows that the latter is more effective, and not because of technology. Singapore combines the app with actual people stationed at the entrance of buildings and shops to verify that people coming in have “signed in” on the app. Hong Kong, still coping with widespread resentment and mistrust of the government after the imposition of the National Security Law and crackdown on political protest, imposed no such enforcement. Few people thus use Hong Kong’s app. Hong Kong has instead relied on periodic spot-checks by police and heavy fines for establishments found with patrons who haven’t checked in to encourage use of the contact tracing app.

Because contact tracing failed to allow Hong Kong to pinpoint likely contacts of those infected, the city has relied instead on overly broad testing mandates, ordering anyone in a building or even a shopping mall at the time of a person with a single infection to submit to PCR tests. But with insufficient staff to carry out these tests, these orders have required residents to gather at test centers, increasing their risk of exposure to the virus. As the Omicron outbreak has resulted in an explosion of infections, these crowds have quickly overwhelmed Hong Kong’s capacity to test them all, leaving the infected to spread the virus even further. It can now take 48 hours or longer to get test results.

So, with its labs, hospitals and isolation center overwhelmed, Hong Kong has turned to China for help. Officials from the mainland aim to beef up Hong Kong’s testing capacity, help it build a temporary isolation facility for close contacts and presumably advise on applying China’s system of localized lockdowns and rapid testing. Unfortunately, Omicron appears to have already spread well beyond any building, housing estate or locale, so using any single infection to pinpoint a lockdown is likely to result in what amounts to the very city-wide lockdown Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam has said she won’t use. And because of Hong Kong’s densely packed, high-rise housing, experts say “vertical transmission” is likely to mean a lockdown at home won’t limit transmission as effectively as isolation in dedicated facilities.

Hong Kong has turned to hotels and property tycoons to provide more isolation capacity, but the logistical requirements of testing, transporting and housing every single infected person seem impossible. Consider that Denmark saw roughly 30% of the population infected since Omicron emerged—and that’s only those it managed to test. Many more cases are likely to have been asymptomatic and never detected. That may be higher than what Hong Kong experiences, since Denmark’s restrictions were light to begin with and its response not entirely convincing. But if even 10% of Hong Kong’s population tests positive, it means having to move, house, feed, test and release roughly three-quarters of a million people on a strict timetable. It’s simply not feasible.

Ultimately, though, it isn’t capacity that has determined the success or failure of Hong Kong’s response. It’s trust. As Ip notes in his article, autocracy isn’t the main reason China has succeeded. It’s trust in the government. That’s why responses similar to China’s have worked in places Westerners perceive as less autocratic, like South Korea (until it relaxed restrictions pre-Omicron) and New Zealand. But it’s trust where Hong Kong faces its most dire shortage.

Russia is moving more forces toward Ukraine, not pulling them out—as Moscow claimed earlier this week. Ukraine hasn’t spotted any withdrawals. On the contrary, the U.S. says 7,000 more troops have arrived, while British intelligence says additional armored forces are moving in. Estonia has spotted battle groups moving into position that it says are part of a plan to occupy key parts of Ukraine. All in all, Russia now has an estimated 170,000 troops poised to invade.

The U.S. has been warning that Russia may need only some pretext to invade, and warned that the attack could come as early as Wednesday. Russia’s envoy to the European Union, Vladimir Chizhov, reiterated Russia’s denial that it plans to invade at all, adding that the Wednesday prediction was in error. “Wars in Europe rarely start on a Wednesday,” he said.

But Moscow may get the pretext Washington says it wants if the gathering forces continue to come in close contact. There aren’t any U.S. troops in Ukraine, but the Pentagon says that last weekend Russian fighter jets flew within 2 meters of U.S. surveillance aircraft over the Mediterranean.

Russia’s aims may go far beyond Ukraine. Russian President Vladimir Putin remains convinced that the time is ripe to roll back the Western advance across Russia’s former satellite states since the fall of the Soviet Union. Ukraine is virtually the last former Soviet republic (other than Belarus and Moldova) that has yet to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Worse, the U.S. has established defensive missile bases in the former Soviet satellites Poland and Romania that it believes could be used to launch offensive attacks on Russia, according to an excellent analysis by The New York Times’ Andrew Higgins.

The timing of his move on Ukraine is now apparent: even as the West was weakened by the pandemic and internal politics, Ukraine was edging ever-close to NATO membership and the new bases were about to go operational. Putin may thus be guided by a historical, strategic and tactical imperative to launch an invasion unless he gets assurances NATO will draw down forces in bordering nations and deny Ukraine membership.